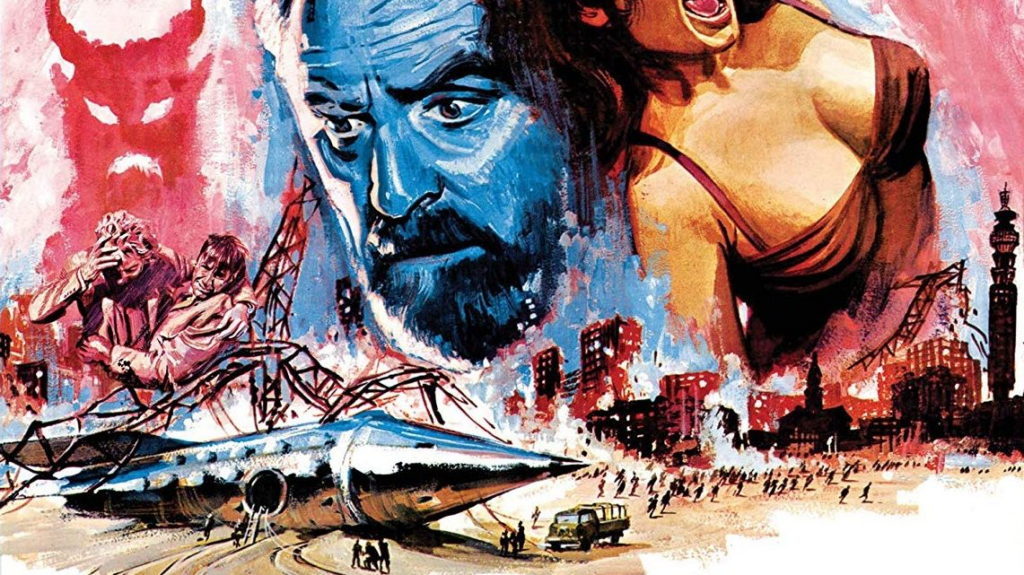

Hammer Films Retrospective (Part V) Quatermass and the Pitt

Doctor Bernard Quatrermass is frequently credited with being the father of Doctor Who. Which used to mean something good. Regardless, this makes the one-time BBC staff writer Nigel Kneale, the grandfather of Doctor Who, and honestly, it kind of fits. A preachy, judgmental, and hypocritical Leftie who is constantly exasperated by the human race’s refusal to “just grow up.”

Nigel Kneale was the creator of the Quatermass serials. His voice was easily and unquestionably the most influential in the shaping of the field of British science fiction-horror. His influence was enormous you can see it in everything from Doctor Who to 28 Days Later. You can even feel a shadow of his hand in Sean of the Dead. And yet, he was at best uncomfortable with his manner of fame.

Kneale wanted the trappings of literary fame. Being toasted by student assemblies at Cambridge. Perhaps an honorary degree from Oxford. Fawning reviews by the New York Review of books. He wanted his fans to be part of a world of high-back leather chairs and expansive mahogany desks, Meerschaum pipes, and fine tobacco by the fireplace.

Kneale never quite adjusted to the fact that his most effusive fans usually weighed 300 pounds and were dressed like Klingons.

He first rose to prominence in the 1950s with the BBC’s adaptation of a book that had been pretty much forgotten called, 1984. The serial starred Peter Cushing as Winston Smith and caused a hell of a stink at the time. “Older and more sensitive viewers” were deeply upset with the BBC, so were the Communists. Controversary interested Hammer Films in the same way fresh blood in the water interests a shark. The rights to 1984 were unavailable but that was okay, Kneale had other works that were . The Quatermass Experiment had been a BBC TV serial first broadcast in 1952. It was also the last time it was broadcast. Back then the BBC was using a new-fangled thing called “videotape.” Except the type of video tape they used was abandoned, so most of the first Quatermass Experiment is now lost media.

…

Regardless, Hammer Films snatched up the rights and hit it out of the park with a black-and-white film version starring American actor Brian Donlevy.

Kneale was not happy with Hammer’s first attempts at Quatermass. Primarily because of Donlevy. Too loud, too brash, and ultimately too American. He had been a film star at one time but those days were behind him. Now he was having to get by in the world of American television and had started to take a serious interest in his alcoholism. He was at best disinterested in his film and the world it was trying to build. In the words of Nigel Kneale, “he took the money and waddled.”

…

The Quatermass Xperiment (Kneale wasn’t in love with the title change either) did great business in Britain, enough to put some real production values into Frankenstein. However, while Peter Cushing’s first outing as a “good doctor” blew the doors off in the United States, Quatermass left us cold for a few reasons.

There was simply no name recognition value for a start. It kind of tasted wrong to Americans for another. It looked like yet another el cheapo flick like The Beast of Yucca Flats, which set expectations for that kind of movie. But it wasn’t, Quatermass was too thinky for tastes that had been trained to expect lighter fare.

But perhaps the biggest is that America is a young country and it affects our view of the world. Americans are intellectually aware that human history goes back farther than 1700 but we don’t feel a bone-deep connection to it. It simply isn’t real to us in the same way it is to someone whose family has lived in the same village since a year that had only three digits in it. America has only ever been called “America,” whereas Britain got its name from Prince Brutus of Troy.

Before that it was Angleland, and before that Albion, and before that elfydd (maybe). My point is this, the ancient feels real to the British in a way that is simply alien to Americans, it may as well be Conan’s Hyborean World so far as our instincts are concerned. And for cosmic horror to work, the ancient is a bedrock requirement.

So while Americans trooped out in droves to watch Hammer’s horror movies, Quatermass remained unwanted drive-in fare. Consequently, Hammer’s second Qautermass movie was also in black and white. While inferior to the Quatermass Xperiment, the sequel did well enough domestically that when the rights to the BBC’s Quatermass III became available Hammer snapped them up. Despite Nigel Kneale’s opinion of the man, Brian Donlevy was once again signed to reprise the role for a black-and-white version of Quatermass and the Pitt.

However, Hammer had become rather dependent on Hollywood for financing, which was a problem because Columbia wasn’t interested in financing it, neither was Universal so the project was shelved. Eventually, the relationship with Columbia went south, and 20th Century Fox stepped in.

By the mid-sixties, the Space Race had warmed up Hollywood’s traditionally cold attitude towards science fiction. Quatermass and the Pitt was on again and in glorious color. Nigel Kneale wrote the screenplay for Hammer himself and much to his delight the possibility of Brian Donlevy returning wasn’t even discussed. Hammer regular Andrew Keir would be taking on the title role. Which was a problem because director Roy Ward Baker had been lobbying hard for another actor. A director who doesn’t want an actor for role always makes for toxic relationship and Andrew Keir described the shooting as “seven weeks in hell.” Although he also granted that they gelled as a unit.

The film opens with some London tunnel diggers finding a human skull. Or not. It turns out the skull is too old to be human.

Gearshift! Bernard Quatermass, the head of the British Experimental Rocket Group is meeting his new boss and therefore actual head of the British Experimental Rocket Group, Colonel Breen (played with dazzling coldness by Julian Glover). Breen is basically a Colonel Blimp, all-flash and thunder signifying an empty head. Breen was an avatar for the distrust the post-World War Brits were feeling toward the military. Or at least the distrust Nigel Kneale was feeling.

Quatermass is appalled to discover that the Lunar colonies he’s designing are now going to be ballistic missile bases. His view is that space is a chance to leave all the icky parts of being humans behind us. Frankly, a better argument would have been that the moon is two days away at top speed which isn’t ideal for a 20-minute response time.

The unpleasant meeting is interrupted by a call; subway tunnel workers have found what is believed to be an unexploded bomb leftover from WWII. This was an uncommon occurrence by the sixties but far from unheard of, in fact, there was a leftover bomb found in Soho as late as 2020. Breen’s job had been bomb disposal during the war, consequently, his expertise had been requested. He went to the sight and declared it an unexploded V-weapon.

Kneale was being lazy here. He was smart enough to write an intelligent character by just writing one instead of having to use dumb-writer tricks. He didn’t have to go with the 3rd rate track of making the people around the smart guy super dumb. Breen had been doing ordnance disposal a mere 15 years before, he would have known what a V-1 and V-2 looked like. He should have shown a lot more interest in the lack of markings or numbers. Those guys were super careful about identifying what kind of bomb they were working on for obvious reasons.

Regardless, Quatermass immediately knew it was no V-weapon. There was also another hominid skull, only this one was inside of the spaceship (sorry, spoiler alert; it was a spaceship). The neighborhood the spaceship is in is called Hob’s End. Hob was an old nickname for the devil. The neighborhood hadn’t been lived in for years. No one would willingly stay there.

Quatermass visits an anthropologist who is so delighted with the quality of his finds that he is ignoring the fact that he now has evidence that Man came into existence in Britain instead of Africa. The anthropologist has a magic brain machine that Quatermass approves of.

Moving along. The spaceship has no machinery at all, it’s just solid “metal.” Although it is metal that leaches energy from any source. Attempts to drill into it power it up. Eventually, it opens up on its own and there are giant grasshoppers in it.

Quatermass deduces that the bugs are Martians and the centuries-long reports of ghosts in Hob’s End are a misunderstood phenomena with a rational scientific explanation behind it, (a theme Nigel Kneale would frequently revisit). Quatermass goes public which sets off a shit storm.

The next morning Quatermass meets with the Breen and the “minister” who are furious with him. Colonel Breen has gone into denial and declares that the whole thing is a leftover Nazi propaganda plan that wasn’t found until now. The minister likes the military’s explanation better than Quatermass’ and goes public with it.

Quatermass, the anthropologist Roney and their super science team sneak into Hob’s End to science the shit of the spaceship with the Brain Machine. Brian Machine gives them some images of life on Mars 5 million years ago and it sucked bad.

Mars was a dying planet, the Martians had tried to colonize Earth but the atmosphere made that a no-go because Martians melt in it. Since their extinction was unavoidable they went with survival by proxy and uplifted (in the David Brin sense of the word) the monkey-boys on Sol 3. However, along with the intelligence the Martians also gave us latant memories and telekinetic abilities. These were dormant in all mankind until coming into contact with the spaceship. It wasn’t as good a deal as it looks on the surface because the Martians were seriously into race purity and ethnic cleansing.

During the press conference, the spaceship finally absorbs enough power to become active. It starts broadcasting its wake signal to the unconscious memories and abilities of every human in London. Everyone who is “different” starts getting killed by everyone else’s newly acquired TK superpower. Finally, a giant ghost Martian materializes over Hob’s End. Roney who had taken over as the hero of the movie decides to try turning a crane into it, the plan is that the energy will discharge into the ground that way, disbursing it.

Roney succeeds but dies in the attempt.

The end.

Quatermass and the Pitt was a movie that turned out to be surprisingly impactful. John Carpenter has claimed it was a major influence on his work. So have talents as disparate as Stephen King and Joe Dante. The creator of the X-Files said it wouldn’t have been what it was without Quatermass and the Pitt.

Counterculture was lightly laced throughout the film with a mix of old and new leftism. Scientist Man was still to be trusted but Government Officials and especially the Military was not. While Baby Boomers got it, the movie really spoke to the British Silent Generation. They spent their childhoods in a war and then were sent to an education system that trained them to govern an empire that had turned to ashes. They spent their entire lives being uprooted and set adrift. The traditional paths forward for the lower middle class of Army, Navy, and even Clergy just weren’t viable anymore. If you had a brain worth draining then it was goodbye London, hello New York but everyone else was lost in a fog. Even the traditional working class felt like it was under siege, anyone from the Commonwealth was now allowed to immigrate driving down wages and sucking up jobs. This resulted in the first genuine race riots Albion had seen for some time.

Quatermass and the Pit spoke to the post-imperial insecurities of a nation.

The critical reception described it as a “well-made, but wordy, blob of hokum” which is high praise indeed for a Hammer Film.

It did well enough that Hammer announced a sequel long before Nigel Kneale had written it. Eventually, the BBC broadcast a fourth iteration during the seventies, I was too bored to see it all the way through. Quatermass was a product of his time and by the seventies, that time was passed.

If you want to watch, it’s widely available… In Britain. It’s been hard to find in America in recent years. The Blu-Ray I picked up had to be watched on my region-free player. It’s not currently available for purchase on Amazon streaming or Apple TV. It is available on the Internet Archive for free, although there are enough legal question marks over that one that I didn’t feel comfortable publishing a link. Just google for it yourself if you’re interested, it should be on the first page of results.

Quatermass and the Pit was the high water mark for Hammer Films, it wasn’t all downhill from there but it was never the same as when it was in its golden era.

Next: Part VI She and One Million Years BC

Previous: Part IV The Mummy