The Death of Disney Animation (Part Three of Two)

If there is one thing that Disney-trained executives universally fail at, it is processing bad news that will remain bad news.

No matter how bad some event is, Disney-trained execs are always going to try and find “a spoon full of sugar” from somewhere. Doesn’t matter if it is an extinction-level event, they are going to view every problem as an opportunity, even if it is obviously an insoluble opportunity.

Optimism is nice and all. But when you are deep in the woods, no cell service, no radio, no compass or map and there is a blizzard coming in. It is not the time to wander slowly around examining the beauty and wonders of nature.

After the abject failure of Soul and the collapse of the Disney channels, the truth that they are magnificently failing to face is that they no longer have the ability to make movies or even TV that children like.

Let me restate that.

Disney (freaking) Entertainment has LOST the kid’s market.

By every conceivable metric (except SJW critical approval), they have lost the audience that built the company.

The reason they’ve lost that market is that Bob Iger threw away his Irreplaceable Man.

Let me start by stating, that I come to bury John Lasseter not to praise him. While he presided over what was nearly a second Disney Renaissance, his time at the company ultimately resulted in leading the animation studios into a pattern of decaying artistic failure.

I’ll try to give credit where it’s due but the breakdown of artistic integrity that Lasseter led is self-evident.

John Lasseter was born in Hollywood. His father was the parts manager at a Chevy dealership and his mother was an art teacher. He appears to have been firmly swayed by his mother, who strongly encouraged him to pursue a career as an artist. He did the usual kid with an artistic bent thing of constantly making doodles and sketches. Interestingly enough he appears to have been a lot more heavily influenced by Chuck Jones than he was Walt Disney.

This is his first film. Lady and the Lamp.

Lasseter was one of the first students in Disney’s incubator program at CalArts. There he was taught and quietly vetted by some very senior animators from Disney. During this period, he also worked as a cast member at Disneyland on the Jungle Cruise as one of the skippers.

He appears to have been quite the Pixie-Duster. He loved Disney and all things Disney-related. When he was formally accepted as an animator at Disney Studios, it was one of the happiest days of his life.

As naturally as a beaver builds a dam, Disney fucked him over.

One of Walt Disney’s innovations for Bambi was a multi-plane camera system that provided animation for the background. Basically, a number of background cells would be moved back and forth while the camera zoomed in or out as needed.

When Lasseter saw the Tron light cycle test footage, he was blown away by the possibilities of computer animation. He immediately began putting together a pitch using this new technique for a version of Where the Wild Things Are. The multi-plane camera was hopelessly obsolete so far as he was concerned.

John Lasseter had just come up with a new idea, at a time in Disney’s history, when that was an EXTREMELY dangerous thing to do. While Disney had once been the great innovator in animation, that momentum had been lost when Walt’s interests began focusing on live-action and the parks. After Sleeping Beauty, Disney Animation became known for its lack of creativity and repetitive storytelling. And this was before Walt Disney died. It became drastically worse during the, “Is that what Walt would want?” Period.

Lasseter’s pitch meeting, barely lasted long enough for Ron Miller to say, “I don’t get it.” Within quite literally minutes of that meeting, Lasseter was told, “Box your stuff. Parking lot. Car. Front gate. Goodbye!” And just like that, his lifelong dream of making magic at Disney was crushed and thrown away like an empty Dole Whip cup. Disney was the only company he had ever wanted to work for, and now it was over.

John roused himself out of his depressed lassitude long enough to trudge down to San Diego for a computer graphics conference aboard the Queen Mary he’d been planning to attend. There he ran into a friend who asked how his ‘Brave Little Toaster’ * project was doing. Lasseter told him.

His friend told him to, “wait here for a second, I gotta make a phone call.”

A couple of minutes later his friend came running back to him and asked, “how do you feel about working for LucasFilm?”

His first project for them was a CGI knight made out stain glass for a sequence in Young Sherlock Holmes. After that Lasseter started working on shorts for LucasFilm’s new subdivision called Pixar. Following a very messy divorce, Lucas had to sell it off to Steve Jobs. Jobs was much more interested in the technical side of things.

It should be noted that at this time, Pixar’s only real product was the Renderman software package. The Pixar shorts were cute and it was nice that they got awards and all, but they were ONLY there to generate eyeballs. In fact, a lot of Pixar’s engineers felt that Lasseter’s stuff was a major distraction for the company’s focus and wanted to get rid of him.

Steve Jobs’ genius was in knowing when to listen to the horn-rim and pocket-protector guys and when not to. Lasseter’s division became Pixar Studios and was expanded when a TV special about animated toys was proposed.

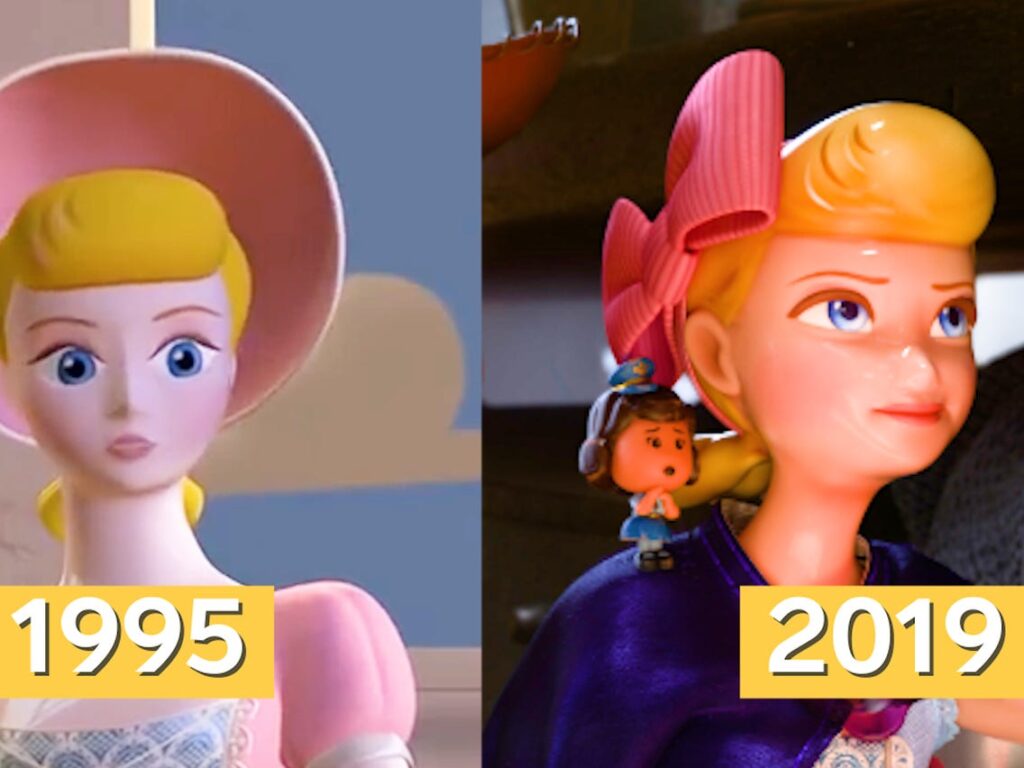

Toy Story came out in 1995… Two years after the first Veggie Tales video. Just putting things in context.

In fairness, Toy Story was the first CG animated movie that was good enough to be considered theatrical quality.

Woody and Buzz arrived at the height of the (so-called) Disney Renaissance. The use of computers for background animation had gone from something that would get you fired for being mentioned to standard industry practice by the 1990s. In terms of art design, it was about Disney’s only real innovation. Calling that period a renaissance is more than a little self-serving for Disney. Sure, the animators were no longer shackled by the things Walt was doing forty years ago. And, yes, audiences were suddenly trooping in to see Disney Animation.

But how good was the artwork when you look at it?

There was genuine innovation in Oliver and Company as well as The Little Mermaid. But by the time Toy Story came out, the life had been sucked out of the artists due to Disney’s crushing one-feature-a-year production schedule. It’s an open secret that The Lion King heavily cribbed its character designs from Osuma Tezuka’s Kimba the White Lion. The stories aren’t the same but the points of similarity in the artwork are too close to be disputed by anyone except a Disney lawyer.

As the Nineties drew to a close there was little more than a burlesque of creativity going on at Disney.

The last movie where I feel the animators were actually trying to “plus it” was Treasure Planet. Yes, the story was bad, and it couldn’t support the film, but it is very much a visual marvel. It was the first new stuff that wasn’t the result of Katzenberg’s treadmill. Treasure Planet was a gorgeous, fantastic mix of CG, hand-drawn animation, and deep canvass. **

Greatly it dared but greatly it failed.

The truth is that it was never going to succeed in 2002, the damage being done to American animation by cheap American, straight to DVD knockoffs was severe in the 2000s.

In the meantime, Pixar had developed a reputation that was based on the quality of their stories and more importantly the infrequency with which you got to see them. They only came out once every three years and they never made sequels.

The company that created the hand-drawn feature, film threw in the towel with the execrable, Home on Range. A film so cheaply made; it was clear that Disney was only trying to gauge if there was any kind of theatrical market for hand-drawn at all.

The next problem American hand-drawn animation faced was foreign competition. “Japanimation” had gone from a niche market for weirdos to completely mainstream.

The last problem was the one that Disney chose to face. Which was, Pixar’s computer-animated features. An ally had become a hostile competitor. So in 2006, Disney bought out Pixar and John Lasseter suddenly had his dream job. He was the new Walt.

John Lasseter’s contributions to the field of animation are kind of a mixed bag. He was working on things that you could do with CG that you couldn’t do with conventional hand-drawn. While he firmly maintains that CG is just a tool, not the driving force, he doesn’t provide a lot of proof for that statement. And there is plenty to indicate that CG is indeed the driving force.

Pixar’s early works favored animating the inanimate. I suspect this was fueled in part by Lasseter’s early success with the Lady and Lamp and his frustration with having lost The Brave Little Toaster. And yet when you look at Lasseter’s Pixar catalog as a whole, the vast majority of his works featured this trope. His directing credits at IMDB are Toy Story, Toy Story 2, Cars, Cars 2. The only film he directed that featured anything alive was A Bug’s Life. The first film that Pixar released that featured humans didn’t come out until 2004 with The Incredibles.

Then there is Lasseter’s preference for “what if” as opposed to “tell me about a guy who.” As a storyteller, he was locked in a pattern of having the setting drive the story.

CG was channeling creativity. It was forcing it to go in a certain direction simply due to its own inherent limitations

Look at this deformed horror from Tin Toy.

Whereas the art design of the Tin Toy itself could at least lend itself to caricature if not outright anthropomorphism.

The same goes for Knick Knack. The figurines in this short were designed in a way that allowed for recognizable exaggeration of physical features.

Resulting once again in humorous caricature.

Lasseter found out early that CG’s biggest contribution was the things that you could do with light. Using computer graphics you could mold light around a character in a way that had never been possible before.

Also, allowing animated features to use live-action theatrical techniques for the first time such as leaving half of a character’s face in shadow.

You could also project light through a character, which simply isn’t possible with hand-drawn.

“Art challenges technology, and technology inspires art.” -John Lasseter.

No, I’m sorry John but it doesn’t inspire art. In truth, it makes real art impossible.

Once the technology worked its way through the “oohs and aahs” of lighting and dynamic background, it was left with no place to go. The reason is simple enough. With the current state of CG, you cannot put one person in charge of a character’s overall design.

One guy is in charge of a character’s lighting, another is in charge of hair, another takes care of the eyeballs, and on and on the breakdown goes. While there is a director trying to successfully mix it all together, there is no one with a cohesive artistic vision for the character, simply because it is impossible to have one. Not when every single thing has to be broken down that far in terms of individual efforts. The fundamental problem of CG versus hand-drawn is on a human level. There is no art to this artwork it’s all machine stamped.

Regardless, the days when Disney concerned itself with artistic merits died with the company’s founder.

The writing was on the wall, the future was computer animation. The 2D animation department at Hollywood Studios was shuttered and Disney moved into 3D computer animation. After Home on the Range tanked the last hand-drawn animation department Disney had was closed.

Here’s the really sad thing. Hand animation has a timeless quality to it that CG simply does not. Take a look at Toy Story or The Incredibles, today. While cutting edge in its day, the CG is so badly dated now that it takes you right out of the story

That never happens with Sleeping Beauty.

There was one abortive attempt to revive 2D with the Princess and the Frog. I’ll give Disney credit; they did try to keep the home fires burning with that one. But sadly, American attitudes at that time still equated hand-drawn animation with cheap straight-to-DVD rubbish. And let’s face it. Everyone looked at the previews and thought Woke. We didn’t have that word yet, but it was obvious that those politics was going to be on the menu at Tiana’s Place.

A few years later Disney shafted Lasseter a second time and this looks like it will be the last. Lasseter is now ruthlessly raiding Disney for its top talent. And it shows at Pixar. Disney’s animation is becoming more and more lifeless.

However, I think there is hope for the future of American-style hand-drawn animation. You just won’t find it in America is all.

Try Spain.

*The Brave Little Toaster is a short story by Thomas Disch, about a bunch of appliances who have been left in the attic. They move around and talk only when humans aren’t looking. The toaster in question decides to set off in search of its beloved owner. I shit you not, Toy Story was that unoriginal.

** Yes, a RE:View of it is on my to do list. Don’t be a pest about it.