RE:View Howl’s Moving Castle

“Calcifer,” Sophie said, “were you ever a falling star?”

Calcifer opened one orange eye at her. “Of course,” he said. “I can talk about that if you know. The contract allows me to.”

“And Howl caught you?” said Sophie…

Roy Disney was the head of Disney’s animation department during the Eisener years. He grabbed that division when Eisner, Wells, and Katzenberg were dividing up the company when the new regime took over. The Last of the Disneys had a genuine appreciation of the art of hand-drawn animation. It was a good thing he did because Eisner and Wells had been thinking about scrapping the whole thing.

Roy was given to financing various foreign animation ventures. Which is how the relationship with Pacific Animation in Japan started. Disney eventually bought it out in the late 1980s. Pacific had been part of the legendary Topcraft. When that studio collapsed, it split into two companies Pacific (eventually Disney Japan) and Studio Ghibli. Since the animators still knew each other, introductions were made to Roy Disney who was quite impressed with Miyazaki’s work. Disney did the financing in exchange for international distribution and ten percent off the top. Thus Ghibli became one of the rarest things indeed, a company with a positive relationship with Disney.

When John Lassetter took over animation he was quite enthusiastic about maintaining the relationship and pursued a prestige format DVD release that made Ghibli a household name in America. It was during this period that Ghibli began making more elaborate productions like Spirited Away and of course, Howl’s Moving Castle.

The film utilizes the first act of the novel and more or less hits the book’s major plot points after that. It’s hardly a word-for-word translation to the screen for the simple reason that the primary audience is Japanese and that is the audience it had to reach. Miyazaki himself thought it would flop in America because it was an anti-Iraq-war movie… Apparently. At least to him, it was. It really isn’t to anyone else. Howl really comes across more as a generic anti-war film, which is fine because most people don’t like it all that much.

Miyazaki’s own experience with war is one of his earliest memories, The Tokyo Firestorm. “The burning ashes of Tokyo wafting in the breeze like hellishly beautiful cherry blossoms, while an entire city is screamed in agony.”

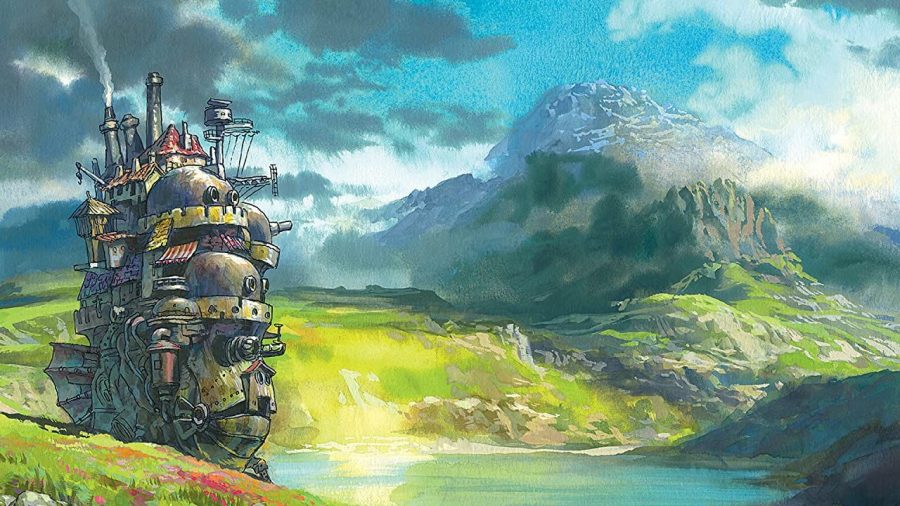

The film opens with a shot of a barren cold windswept moorscape. There is grass, rocks, and mist evident but not much else. Then we hear a chuffing, puffing, and clanking of a steam-powered something. Some-thing is right. We see our first glimpse of the four-legged grotesque, mechanical steam steam-driven Golem on acid that is Howl’s castle.

The audience is treated to some gorgeously detailed world-building shots. The setting is gaslamp fantasy.* I suspect the Japanese are particularly drawn to this because of the Taisho Era from the turn of the last century.

Emperor Taisho ruled over a time of relative liberal progressivism in Japan. As an example, when the Japanese captured some Germans in WWI, the POWs were not only treated humanely but so much so, they stayed on after the war and founded Japan’s beer industry.

The Taisho era was a time when automobiles, electric lights, and western business suits could end at the edge of a neighborhood and you’d be walking in a world that seemed unchanged since the 1300s. It was a place where the ultra-modern was constantly rubbing shoulders with the ancient beyond measure. This was still a place where honor meant more than life. Japan was trying to invent a new place for itself in the world and for that matter, its people were all having to find new places for themselves. Everyone from the Samurai to the criminal underworld was having to come up with a new way to be Japanese. Things couldn’t keep going the way they’d been but they didn’t want to let go of what they had been. There were old men who had living memories of the Tokugawa Shogunate. These people wanted to move forward but still have their feet planted firmly on the earth.

So, the setting is kind of half magical to the Japanese to begin with.

We arrive at Sophie’s Hatter’s hat shop. The other girls in the shop are commenting in excited whispers about the wizard Howl’s castle that they can just barely see traversing the Wastes. He’s clearly somebody exciting, daring, and quite frightening.

In the original novel, Sophie lives in a magical land where all the tropes of fairy tales come true. Since she is the eldest of three sisters she is destined to have a dull and uneventful life. She has accepted her boring fate and is resigned to it.

This is the aspect of her character that Miyazaki latched on to. Miyazaki generally favors a female point of view character. A young girl who goes on a journey and grows in consequence of it. It’s not really a Campbellian Hero’s Journey, those have very distinct inciting incidents that his heroines don’t have. But they do grow as a result of their adventures.

At closing time Sophie goes out to see her sister. The army is in town because there is about to be a war with the neighboring kingdom (their crown prince has gone missing and they’ve blamed this kingdom for that). A couple of soldiers try to pick her up, they aren’t particularly villainous in aspect. In the English language version, they are threatening but in the Japanese, it’s more friendly.

Howl appears, puts an arm around her, and calls her “sweetheart.” He sends the soldiers marching away with a gesture.

There’s an interesting little detail here. Later in the movie, Howl gives Sophie a ring that will always show her the way to his heart. However, in his first scene, it is Howl that is wearing the ring and it’s glowing.

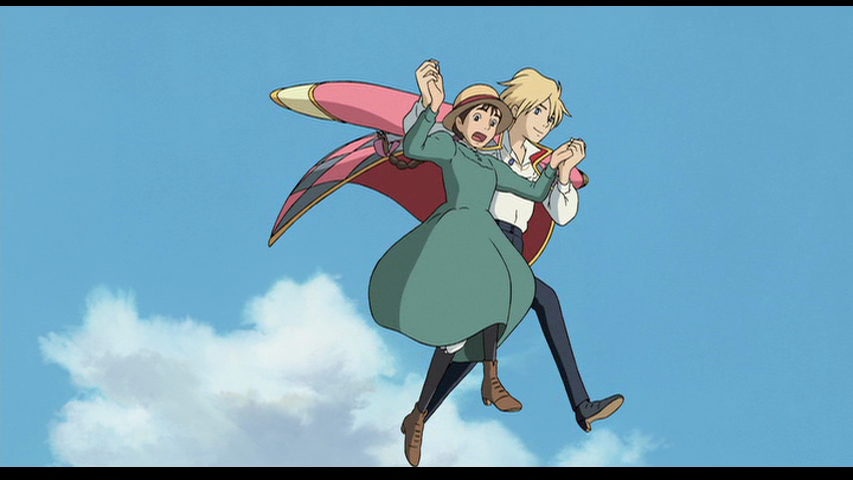

Howl asks Sophie to walk with him and “just act natural.” He’s being pursued by some Ghibli Tar-Blob Monsters. They block him off and Howl puts an arm around Sophie and they take to the air.

This scene is a huge fan favorite. Howl tells Sophie to just start walking, she’s terrified but doesn’t freeze up in this impossible situation, she walks in time with Howl, dancing through the air. Taken far above her native element Sophie she can still function. Consequently, you aren’t surprised when she continues to do so later in the movie.

Howl drops off Sophie at her home.

When she goes to her hat shop she runs into a grotesquely hyper obese woman. This is the terrifying Witch of the Wastes and she places a curse on Sophie. When the young woman wakes up in the morning she discovers that she has become an old woman overnight.

I think the nature of the curses may have been what attracted Miyazaki to this property in the first place. They are the worst imaginable because they turn people into a physical manifestation of what they truly are. Sophie is a young woman who lives so much like an old woman she effectively is one. The Witch of the Waste uses glamour spells to make herself appear young and powerful but really isn’t. The prince of the neighboring kingdom was turned into the brainless, good-hearted scarecrow Turnip Head. Howl himself is cursed with heartlessness in both the literal and figurative senses of the word.

A curse that reveals your truest self is a long-standing theme of Miyzaki’s. You see this in Spirited Away and Porco Rosso as well. Variations on that theme are evident in his other works.

Sophie responds pretty well to her curse all things considered. She sneaks out of her home and walks into the Wastes. In this film, the Wastes are clearly a place of the uncanny and the magical. It’s not safe there but it’s the only place she’s likely to find Howl, who had shown interest in her and was probably powerful enough to break the Witch’s curse.

This is where she helps the scarecrow out of some brush and he turns out to be magical. She names it Turnip Head and asks it if it can find her someplace warm to sleep. It leads her to Howl’s castle.

She meets the fire “demon” Calcifer (Demon is a little wide of the mark as direct translations go). Calcifer makes a deal with her, if she breaks the curse that binds him to Howl, he will break her curse. He can’t tell her the details because of the curse, she has the same problem. In the morning she meets Howl’s boy apprentice and finds out that the door to the house leads to other places depending on where the door’s dial is set. This was also from the book and it is where the resemblances to the novel ends.

The middle is definitely a muddle. It’s mostly a prolonged mosaic of scenes constructing a child-friendly anti-war diatribe. The funny thing is that is genuinely child-friendly. It clearly draws heavily from Miyazaki’s own memories from earliest childhood where it’s mid-day but the smoke is so thick it blotted out the sun. It’s all perpetual darkness and fire. His childhood mindseye of war is a literal hellscape. But does not have any graphic horror.

As her story progresses Sophie stops reacting to circumstances that have been inflicted on her and takes the lead. This is the point where she begins breaking the curse, becoming younger as she struggles against and overcomes the increasingly difficult challenges inflicted upon her.

Eventually, she discovers that Calcifer is Howl’s heart, and his moving castle is part of an elaborate defense that protects it. But without a heart Howl is vulnerable to losing himself. He becomes a monster when he fights and he is close to becoming one forever.

Sophie uses the ring Howl gave her to find her way to his boyhood and discovers that Howl had swallowed the fallen star Calcifer which is how he’d lost his heart. Sophie cries to him to find her in the future.

Back in the present AKA the future, Sophie restores Howl’s heart, breaking his curse. She had already broken her own, however, her hair stayed silver indicating whatever you want it to indicate. Turnip Head turns back into a prince when Sophie gives him a peck on the cheek, thus ending the war. Calcifer is now sticking around Howl because he wants to and the film ends with him powering a now flying castle. Howl and Sophie kiss.

I’ve heard that the author was privately dissatisfied by Miyazaki’s adaptation. I would have been surprised if she wasn’t. Hayao Miyazaki wasn’t telling the same story that she, was even though he did go out of his way to hit a lot of the plot points that Diana Wynne-Jones had made in her book. Howl would spend hours primping and preening in the book to make himself beautiful. While that aspect of him did make it to the screen it’s a bit out of place with the story that Miyazaki was trying to tell. There are other things like this.

At the end of the day, an author whose work is adapted to the screen has to swallow the bitterest of pills. It’s never going to be your art, the best you can hope for is to inspire another artist.

*Gaslamp fantasy is steampunk but with magic.