Hammer Films Retrospective (Part IV) The Mummy

“Cursed be those who disturb the rest of a Pharaoh. They that shall break the seal of this tomb shall meet death by a disease that no doctor can diagnose.” – Translation of the Curse of Wadjet.

That was the actual curse placed upon those who would dare disturb the tombs of the pharaohs. It didn’t seem to widely disturb the tomb raiders’ brisk trade in antiquity. For that matter, the very worst tomb raiders were the Egyptian priests themselves during the last of the Pharaonic dynasties. So, while there was a mummy’s curse, even back then no one took it seriously. Although interestingly there was at least one cursed mummy. Akhenaten has been tentatively identified as the Mystery Mummy of KV55. All of the mummy’s names and protective spells on that sarcophagus were ritually chiseled away. Leaving only the eyes intact. Akhenaten while a god in his own right was a despised one, and was at best a very undesirable stand-in for Osiris. His reign and the decades following were a time of great instability for Egypt, clearly, everyone blamed Akhenaten. However, when his son, Tut, died and became Ruler of the Kingdom Beyond, it is surmised that special rituals were needed to imprison this mad god’s Ka and Ba within his own remains.

So, there was a little something to Hollywood’s fantasies about The Mummy, granted it was only arrived at by accident.

By 1798, the kingdom of Kemet was in truth a lost civilization. Its kings, its gods, and its history not even surviving in legends. All of it had faded into oblivion around the 7th century AD when the admittedly cumbersome hieroglyphics were finally abandoned.

Unrestricted immigration had reduced the native population of Egypt to a few Coptic settlements, the invading tribes viewed any relics from before the time of the Prophet as objects from the Age of Ignorance and should probably be destroyed but there was just too much of it around to be worth the effort. Although treasure hunting definitely was worth the effort and you never knew what you’d be accidentally burying with uncontrolled demolition.

Academic interest in Egypt revived somewhat during the Enlightenment, but there wasn’t much to work with as the language of the hieroglyphs was completely lost. A few half-understood myths left over from the Greeks and Hebrews were all that was left of the Land of the Pharaohs when Bouchard discovered the Rosetta Stone.

But that relic changed everything. Western civilization went Egypt crazy. It seemed as if vast repositories of ancient knowledge had suddenly been thrown open. There was a mania for all things Egyptian. Its influence on architecture was almost instantly felt, Doric and Ionian columns were suddenly hopelessly obsolete. New obelisks were suddenly invading graveyards for the first time in 2,500 years. The Masons got super excited when they found out about the Eye of Ra and started inventing vast tracts of their own history. Jewelry and furniture that would have been at home on the Nile in Ramses day were being seen in the finest homes.

And then there were the mummies. Mummies became a huge part of the society scene. They were taken from Egypt and brought to the country’s manor houses. There were Unwrapping parties where the well-to-do would get together and watch as some professor or another snipped away the ancient wrappings revealing the desiccated remains contained therein.

There was even an artist’s pigment called Mummy Brown, described as “a rich brown pigment with a warm vibrancy. The colour is intermediate in tint between burnt umber and raw umber. It has good transparency, and can be used in oil paint and watercolour for glazing, shadows, flesh tones, and shading.” The primary ingredient was indeed ground-up mummy.

Then there was the truly goofy-as-hell stuff that Egyptomania did to the 1800s Spiritualism movement. I have nowhere near enough space in this article to go into the rantings of Madame Blavatsky about Egypt and Atlantis except to say that it was heavily mined by Heinrich Himmler when he was inventing the SS’s religion.

Time moved on; the Egyptian Antiquarians were pushed aside by the Egyptologists, excavation standards were adopted, not “disturbing the dead” became a popular taboo, and a general “Are we the baddies?” energy settled over the memory of 19th century’s Egyptomania.

“Death shall come upon the swiftest wings to him that toucheth the tomb of the Pharaoh.” The Curse of King Tut’s Tomb

Dark Hearld: Did you know my beloved Darklings, that everyone who entered the Tomb of King Tutankhamun… HAS DIED!!!

Darklings: Yeah, we did. Tut’s tomb was opened in 1922. Anybody who went into it would have been well over one hundred twenty years old at this point. It would be a lot more worrying if they weren’t all dead by now.

Okay, I admit that curse was total bullshit. It was created by a reporter for the New York Times who wanted to punch things up a little. But it did reflect the spirit of the time, the general air of regret for having done things that shouldn’t have been done.

A feeling of, if the ancient and defiled dead of Egypt are not angry with us, they certainly have a right to be.

There were several mummy-themed films in the silent era some predating Carter’s find, although most are now lost media. I’m honestly rather surprised to discover that The Mummy (1932) was an original story and NOT than something that got recycled from the silents.

Of the first three Universal monster movies, The Mummy is arguably the best. It has certainly held up better than the James Whale films. The story is an intriguing one; forbidden love that is stronger than death. In the 1932 film, Imhotep is a fully sapient revenant and has the use of unholy powers by means of his dark magic.

Surprisingly Karloff’s version went away in favor of “Kharis” the more common, foot-dragging, zombie-mummy in The Hand of the Mummy. At least until Imhotep returned in 1999.

Anyway, Kharis took center stage at Universal Studios for The Mummy’s Tomb, The Mummy’s Ghost, and The Mummy’s Curse. Kharis’ last appearance in the Universal films was in Abbot and Costello Meet the Mummy (1955). Being made a third banana in a 50s screwball comedy was quite a comedown in the world for this prince of Egypt.

However, Kharis would rise again in four years for Hammer Film’s The Mummy.

You will note that this time there are no adverbs or adjectives front-loading the title.

The huge success of Hammer’s Frankenstein and Dracula films had made Universal Studios have second thoughts about the little film company that could. Hammer’s The Mummy was made with the full cooperation of Universal. Which was fairly important for this intellectual property. While Dracula was a historical figure and Frankenstein was in the Public Domain, Kharis was an IP firmly in the control of Universal. While it’s true that Imhotep was a historical figure as well, his use as a mummy would have been an obvious infringement.

As I said, “Money cures all in Hollywood.” So long as Universal was getting it’s zero-risk cut, Hammer Films could do as they liked.

Michael Careras immediately rounded up his A-team from Curse of Frankenstein and Horror of Dracula. Jimmy Sangster pounded out the screenplay while Terence Fisher settled in to direct and Jack Asher was behind the camera ready to work his magic with Eastman Colour.

Peter Cushing was signed to be the Egyptologist leading man John Banning with French beauty Yvonne Furneaux in the duel role of Elizabeth Banning/Princess Ananka.

And for a change, there was absolutely no problem with Christopher Lee. He was intrigued by the part, for once he was genuinely enthusiastic about working on a Hammer Film.

There was genuine depth to the character he was playing. Kharis the priest who had dared to love a sacred virgin forbidden to all by Mortal and Devine law. He defied death itself to steal back the woman he loved from the Land of the Dead. For these acts of both treason and sacrilege, he was given the worst of all possible punishments, immortality.

There were two things going on with Lee at that time; when he was in Hollywood for the premiere of Dracula, Boris Karloff had told him about the advice Lon Chaney Senior had given to him – “find something other actors can’t or won’t do. If you succeed, you’ll never be forgotten.”

The other was that Christopher Lee had seriously gotten into J.R.R. Tolkien, who had befriended the young actor. Lee was (reportedly) intrigued by the concept of Ilúvatar’s gift of Death to Mortal Men. That Eru’s great gift was that the corruption of a man must die with him. There could be no worse curse than to carry your mortal corruption with you into immortality. It was Kharis’s unreachable desire for redemption that Lee found fascinating.

The film started with the standard pith helmet-wearing expedition into the Egyptian desert to find an ancient cursed tomb just ripe for disturbing. In this case Universal Studio’s Princess Anaka. The dig was going well but Young (Banning) Peter Cushing had broken his leg and was going to have to be evacuated because it was showing signs of infection.

His father and his father’s best friend are about to enter the tomb when native Egyptian Mehmet Bey enters the scene and demands that they don’t defile the tomb, vague mystical threats are made but being good Victorians they ignore them completely and enter the tomb.

The best friend goes to inform young Banning while old Banning does the reading the Forbidden Scroll thing setting Kharis loose. Old Banning screams and has a mental breakdown.

Young Banning finishes the dig for his now broken-down father. When the excavation is complete, Peter Cushing, because he gets a bad feeling about the place, BLOWS UP THE TOMB. As Egyptology goes this is actually worse than that of Stargate.

Back to England, they go and Mehmet Bey follows him with a 6’5 inch crate in tow. Cushing goes to see his father who has been catatonic since the dig in Egypt but has been roused by something. He tries to warn his son and Cushing is too Victorian to take it seriously. Bey reads the “Scroll of Life” and I did recognize a few quotes from the Book of Going Forth by Day (AKA The Bood of the Dead). The writer Jimmy Sangster approached this project with either some cultural respect or thought it was easier just to crib.

Kharis Goes Forth by Night and kills the elder Banning in his nursing home.

Time for a flashback. While Peter Cushing narrates Christopher Lee is finally permitted to establish a character in a Hammer film. Princess Ananka had already died, so we start with her embalming ceremony, while Lee gazes longing at his love and reads actual Egyptian hymns, (the scholarship wasn’t as terrible as it usually is for these things). We also see authentic members of the Egyptian pantheon taking their place in the cortege while Kharis contemplates his unspeakable blasphemy.

Now there was quite a bit of made-up bullshit in this ceremony. There was quite a lot more human sacrifice than was customary for Egyptian religious ceremonies. Pre-dynastic Egypt used to do that but it fell out of fashion in favor of Ushapti statues, which had already been featured in Anaka’s funeral procession.

I was a little curious where Hammer found their “Nubian Slaves.” They weren’t that common in Britain in 1959. It turns out Hammer Films was famous for emptying out nightclubs and restaurants when they needed ethnic extras. The wait staff for their part liked the extra pay and a chance to be in showbiz for one scene or two.

The ceremonies concluded, Kharis does the unthinkable and nearly succeeds when he is caught and sentenced to his horrifying fate.

Back to the present or at least 1898. Mehmet Bey sends out Kharis to kill the remaining Egyptologist who had defiled Anaka’s Tomb, which he does. Cushing catches him in the act and now knows the truth of it. Nobody else believes him but that’s to be expected in this kind of movie. Kharis is then sent after Peter Cushing blowing up Anaka’s Tomb being a bigger deal than just entering it, but as monster movie law would have it, his wife is a dead ringer for Ananka. So, Kharis obeys her commands to stop killing Cushing.

There follows an interesting scene with Cushing and Bey when the younger Banner visits him at his home. There is an exchange of viewpoints about science and how far it should be allowed to go. Cushing leaves and Bey decides that Kharis will need personal supervision next time.

After a lop-sided fight scene, Kharis is strangling Cushing again when his wife stops him again. Bey orders Kharis to kill the girl who looks exactly like his beloved princess.

Yeah, wrong call. Kharis takes it badly and breaks Bey’s spine. The wife faints and Kharis takes her into the swamp for whatever reason. Cushing and the police catch up to them and some obvious instructions are shouted to the wife. She tells Kharis to put her down. He does and then Kharis wanders off alone into the marsh never to be seen until the sequel.

While The Mummy did brisk box office traffic, Christopher Lee would not be coming back. His early enthusiasm for the project flagged when he started getting the shit beaten out of him during the production. Rising from the marsh when he is first summoned by Mehmet Bey, you see Kharis take a very halting step and stop suddenly. I wince when I see that now. The marsh was Hammer’s jungle movie set and there were underwater pipes throughout to send bubbles to the surface. Christopher didn’t know where they were but his shins certainly found out. Constantly. A bigger problem was when he attacked Peter Cushing for the first time. Kharis crashes through a pair of doors. They were supposed to be breakaway doors and weren’t. Lee dislocated his shoulder breaching real doors. He was burned by the squibs when he got shot. And finally, he bashed his knees bloody on the underwater pipes again when Kharis had to go back to the swamp.

Christopher Lee. Was. Out.

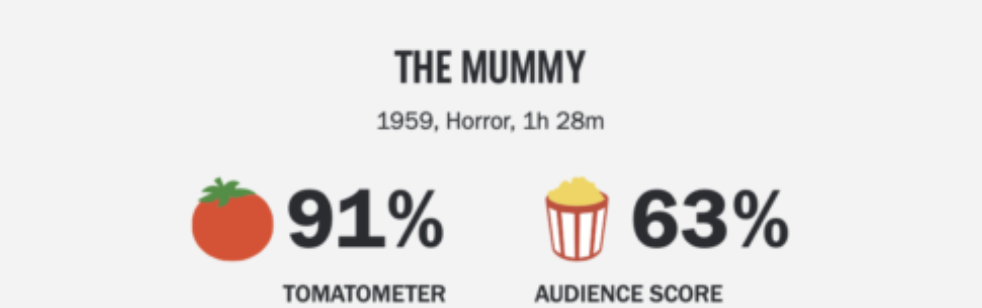

The critical reception wasn’t as bad as it had been for Hammer’s Frankenstein and Dracula. Nowhere near the level of vitriol was unleashed this time. The reviews weren’t good you understand but the critics had clearly resigned themselves to the fact that Hammer Horror wasn’t going away on their sayso, continuing with the diatribes just made them look weak and ineffective. In the long term, they were right to be concerned.

Previous: Hammer Films Retrospective (Part III) The Horror of Dracula

Next: Hammer Films Retrospective (Part V) Quatermass and the Pitt