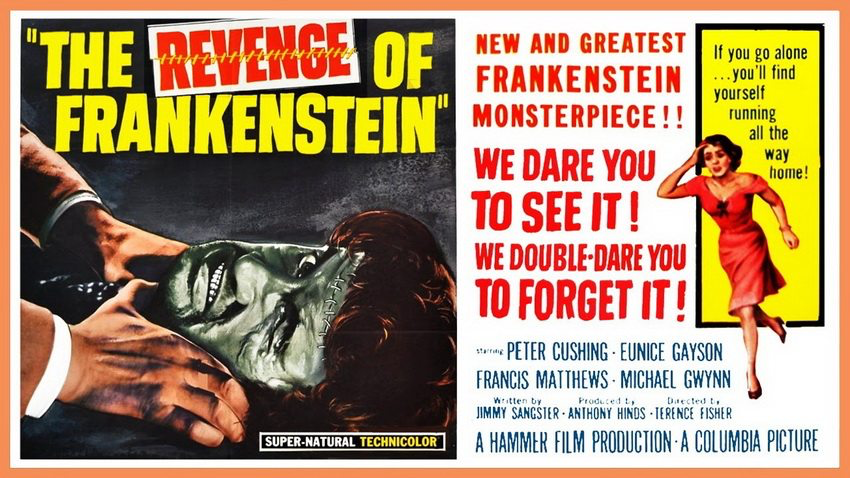

Hammer Films Retrospective (Part II) Frankenstein Rises!

His nickname was “Props Pete” because of his preferred method of performance. Most actors only interact with props if a director gives them specific instructions to do so. But Props Pete was forever picking up this item or that one during a performance and used it casually with apparent long-accustomed familiarity. It added depth to the role he was playing. He was trying to sell the audience on his character being an expert in whatever field the part was meant to be brilliant in.

That peculiar little affectation as well as his thin, hawkish features and his sad but intelligent eyes tended to typecast him in Scientist Man roles. Most of his 131 credits on IMDB were for characters with Doctor or Professor in front of their names.

So far as Peter Cushing was concerned this was more feature than bug because typecast actors were never out of work.

That isn’t the only thing he ever played of course. Those same looks occasionally got him roles as war criminals who committed unspeakable crimes against the human race.

And if it wasn’t for Star Wars, he would be best remembered for a performance that combined both.

Baron Victor von Frankenstein.

In the mid-fifties, Hammer Films had run into a consistent problem with the British government. The Film Board’s X certificate. The board was very, very liberal in applying this “adults only” rating. Just to make things clear to my younger Darklings, the X certification in this case was not applied to pornography. Porn was covered by indecency laws that were still rigidly enforced in those days. No, this ban on anyone fifteen-years-old and below was applied to the same things that the American Comics Book code would find objectionable.

Hammer decided that since they were so frequently stuck with this lemon of a rating, they should make lemonade. They leaned into it as far as the laws of the UK and public tolerance would allow in those days.

The recent success of the Quatermass films had left the ‘little studio that could’, quite flush with cash. Enough so that they could afford to shoot the first of their monster movies in glorious Eastman color (I still love that palette). This was at a time when most B-movies were still shot in black and white.

The plan was for a series of movies based on classic monsters that were in the public domain. All well and good. Hammer Films could only work on one film at a time, so they decided to do Frankenstein first due to the subject matter’s inherent opportunities for blood and gore.

Then out of blue, Universal Studios did the biggest favor it possibly could for Hammer Films. The American studio had gotten wind of the production and sent Hammer a long, multi-page letter detailing the vast amount of things they would consider infringement on their version of Frankenstein. And would in consequence sue the unholy fuckity fucking fuck out Hammer Films if they crossed even one of those red lines.

This turned out to be the best thing they could have ever done for the Curse of Frankenstein because it forced the studio to go light years out of their way to make their version of Frankenstein completely unique.

The only thing that Universal couldn’t block were those few things that could be lifted directly from the 1818 novel by Mary Shelley. Which was fine but all that the general public knew about Frankenstein were from Universal films of the thirties. Hammer couldn’t put any of it in their film. No hunchback assistant, for instance, he had to be young and good-looking.

Hammer didn’t even dare use the unadorned title, ‘Frankenstein’ hence the name change to the Curse to Frankenstein.

The first problem was the Baron himself. He had to be the polar opposite of Colin Clive’s portrayal. Clive’s Baron Frankenstein was given to hysterics and peels of mad laughter, yet in some ways, he wasn’t too far from Shelley’s creation. Both Barrons were too obsessed with their work to realize what they were doing was wrong until the creature was brought to life. Only then did they realize they had crossed lines that should never have been crossed. Both became to one degree or another penitents for their crimes.

Cushing’s Baron Frankenstein on the other hand was so high on the Dark Triangle, he could look down at Everest. He was fundamentally incapable of remorse and was clearly an ironclad psychopath, he was born without a shred of human empathy, and he had the hubris needed to rebel against God Himself. He was utterly ruthless in pursuing his desires. While he was planning to marry his aristocratic cousin Elizabeth, he was having his way with her maid, Justine. When Justine became pregnant and threatened to tell Elizabeth about her condition and who was responsible for it, he locked her in the same cell as his monster knowing full well that whatever it did to her, she wouldn’t survive it. The film was explicit in identifying Victor Frankenstein as the real monster. Right after he had murdered a woman who was pregnant with his child in the most horrifying way possible, the next morning he is having breakfast with Elizabeth.

“Pass the Marmalade, would you please Elizabeth?

The absolute lack of human compassion demonstrated in that one little request was more shocking than a pyramid of skulls would have been.

Hammer needed to find the right man to play the part. And nearly made the disastrous mistake of hiring another American. Fortunately, a BBC actor named Peter Cushing got wind of the project and started campaigning hard for the part. He threw himself into the role with ferocious passion. He rewrote a lot of the Baron’s dialog and even went so far as to extensively coach the child actor playing the Young Victor Frankenstein. Which worked fantastically by the way. The character flows seamlessly from Young Victor to Doctor Frankenstein, they are obviously the same person.

Director Terrence Fisher knew a great thing when he saw it and got out of Cushing’s way, giving the actor the space he needed to deliver the performance of his life.

Fisher along with his lead, his production designer Bernard Robinson, cinematographer Jack Asher, and composer James Bernard created Hammer’s distinct and unmistakable aesthetic. You know within minutes whenever you are watching any Hammer film, be it a Frankenstein film or one of the Draculas or even Slave Girls of the White Rhinoceros (I’ll get to that later don’t be a pest about it).

Now that Fisher had his lead actor, he’d need his monster. Since the monster was mute the only thing that was needed was someone tall and athletic. Enter the struggling character actor from an aristocratic background, name of Christopher Lee. At six foot five, he was the second choice but the guy who was six-seven was unavailable. It would be the first of many collaborations between Cushing and Lee over the next thirty years and the beginning of a life long friendship between the two men.

Boris Karloff’s iteration was almost childlike in its innocence, you had no trouble pitying the poor thing for its wretched existence. Lee’s creature on the other hand was a mindless vicious brute. If Baron Frankenstein was all superego, this creature was from his id. He would kill you just for being near him. The creature’s design was that of a patchwork monster stitched together from a trainwreck. A golem made of flesh. A soulless abomination. Not an imitation of God’s work but a mockery of it.

The plot of Hammer’s first film was meant to be a stand-alone feature without any plans at all for a sequel. It begins with Frankenstein begging a priest to hear his story on the eve of his execution. The final scene is the *fallbeil blade falling.

The Curse of Frankenstein was released to universal revulsion and disgust.

“I can no longer defend the cinema against the charge that it debases…”

“Depressing and degrading for anyone who loves the cinema.”

“Among the half dozen most repulsive films I’ve ever seen…”

The British public chose to ignore the critics and the film broke records. In the US it did so well that it grossed something like seventy times its production budget. Hammer was out of the quota-quickie business and was now the home of the best gothic horror the fifties would see.

Money makes everything better in Hollywood. When Universal Studios saw the gross receipts for Curse of Frankenstein, not only was all forgiven but they would happily kick open the film vault door, provided Hammer would sign an exclusive distribution deal with them. This was a good deal for both sides. Universal got zero-risk profits and Hammer got access to all of Universal’s monsters with no strings attached.

There was only one problem. Universal wanted to know when they were making the next Frankenstein movie.

Why let a little thing like a beheading stop you when there was that much money on the line?

Next: Hammer Films The Horror of Dracula

Previous: Hammer Films Gothic Beginnings

*The German version of the Guillotine. Since this was a Hammer Film it probably was a Guillotine come to think of it.