RE:View – Doppelganger

If you were growing up in the Seventies and had been cursed with a love of science fiction, your battle cry was, ‘you get what you get and you don’t get upset.’ There just wasn’t much to be had for most of that decade. Consequently, what little was available tended to make a strong impression.

If you were lucky, you lived someplace where a UHF station would have a dedicated afternoon movie slot. The one in my neck of the woods did. However, the programming manager appears to have had a weakness for European sci-fi. I saw a lot of titles when I was a kid that were little more than a rumor to the rest of the US. The Quatermass movies, the (Peter Cushing) Doctor Who films, Day of the Triffids, Village of the Damned, The Damned (most anything by Hammer). Plus, some other titles from Italy like Tenth Victim and Planet of the Vampires.

So, it’s not surprising that Journey to the Far Side of the Sun was in rotation on Saturday Afternoon Sci-Fi Drive-In Theater.

British sci-fi films tended to be qualitatively better than American sci-fi of the period. Largely because American sci-fi didn’t exist and what little that did was stuff like The Beast From Yucca Flats. There were a few exceptions like Forbidden Planet. But not many.

The English looked at what Hollywood wasn’t doing and did that.

The British film industry was chronically underfunded until around 1950. A lot of that was class-driven. Money goes where the moneyman’s interest is. The London moneymen didn’t want to associate with theater and music hall people. The UK government never showed much interest in promoting it either. However, the protectionist policies of the Attlee government created a situation where Hollywood studios owned money in England but couldn’t bring it to America because money made in Britain had to stay in Britain. They were however perfectly free to spend that money… in Britain. Consequently, it was worth Hollywood’s while to inject a little capital into Brit productions that were halfway funded through local accounts, to begin with, then bring the film to the US. And Americans could mostly understand English back then. Walt Disney aggressively pursued this strategy, creating films like Darby O’Gill and Treasure Island. United Artists hit it much bigger with James Bond.

Consequently, there were British film projects that should have had a lot more trouble getting money but didn’t. Like Doppelganger.

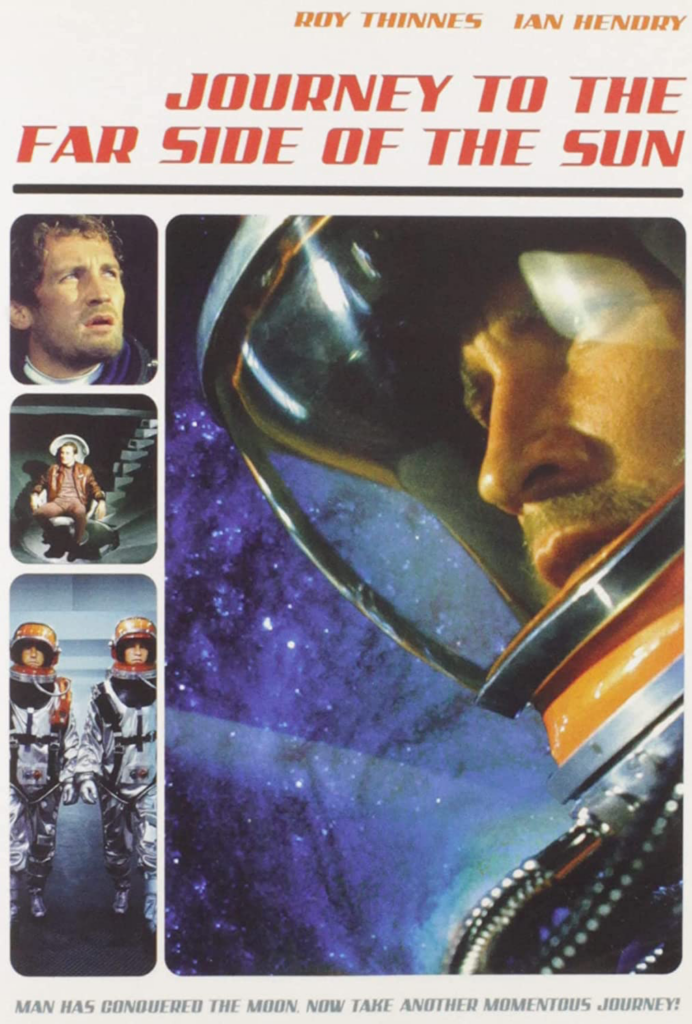

I hadn’t really planned on April being Gerry anderson month but in for a penny, in for a pound, and truth be said, I’ve found unexpected enjoyment in revisiting some of my childhood friends. We are now moving past Anderson’s Supermarionation days. Doppelganger or as it is better known in the US, Journey to the Far Side of the Sun, was Gerry Anderson’s one shot at the big brass ring.

And he missed.

This film is reflective of the prevalent science fiction tropes of the Sixties. The slightly psychedelic question of “How do I know what is real?” is a central question of this film. 2001 had been released the year before, so its influence is minor, but it is there. Everyone knew it was coming for a while. In some ways, Doppelganger is more reminiscent of an episode of the Twilight Zone. This isn’t a surprise because it started life as a one-hour TV special.

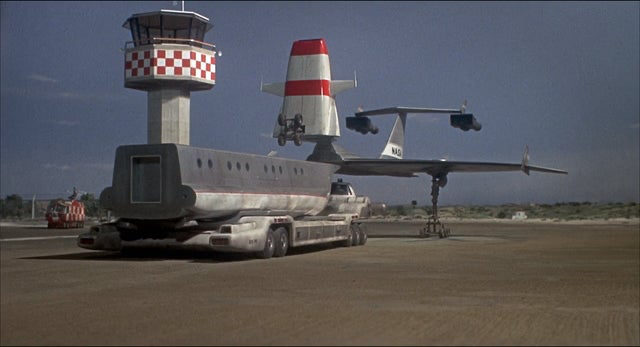

It’s an interesting little crossover film between Button-down Sixties and Spacey Seventies science fiction. For instance, the clothing pretty much came off the rack; thin ties with two-piece suits and mini-skirts. But the sets reflected the kind of James Bond futurism you would see in The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker. There was a supersonic airliner that had VTOL capability and in true Thunderbirds fashion, the passenger section detached and went to the terminal separately.

The film starts with some Cold War movie tropes. Herbert Lom is admitted to a top-secret facility after a neck-down body scan shows he isn’t carrying anything. Once there he starts taking pictures of the controlled materials using a camera concealed in a false eye. Barry Gray’s music score is great by the way, he nailed it in this movie.

The next scene is a pow-wow of something called the European Space Agency. The CI stuff was a Top-Secret astronomical discovery! There is a planet on Earth’s orbital path, exactly on the other side of the Solar system. The British head of the agency wants to send a manned expedition to it.

This movie has a lot of pretty big asks for its audience and what it mostly keeps asking is that you don’t think about any of it too much.

The Germans don’t want to waste money on it and the French back their play. The Americans aren’t wild about the idea in general. However, Director Webb knows he’s got a leak, so he gives access to the most likely suspect, (Herbert Lom). The spy spies on Compartmentalized Information and gets shot for it.

That was a bit of a what the hell? Moment. No attempt at arrest or trial. Just a sanctioned hit in a Western country because he’d been caught red-handed? Apparently, Anderson thought or at least assumed Western audiences would accept that that was how things were done. If you had the option back then you captured a spy, squeezed him, and then traded him back for your own guys. But some bureaucrat needed funding so Herbert Lom got shot up and stuffed in the bag. I wish I could say that doesn’t ring true.

Webb lets the American representative Poulson know about the breach and the plumbing job. But obviously, the “other side” knows about the planet and will launch their own expedition to it.

Such an odd little cliché of the period. Movies and TV would sometimes go miles out of their way to avoid saying the words “Russian, Communist, or Soviet.”

But since “they who must not be named” are going to launch an expedition the dim-bulb Americans kick open the money spigot by Pavlovian reflex. Poulson was played by the Anderson’s favorite rent-a-Yank, Ed Bishop who would be leading the fight against the aliens in UFO the next year.

Poulson does have a demand, the pilot in command would have to be American super-astronaut Colonel Glen Ross (Roy Thinnes). Director Webb has no objection to this at all. He seems to regard him as genuinely being the best man for the job. However, the co-pilot will be his right-hand man John Kane.

This was the first time that Gerry Anderson got to play with adult themes and play with them he did. Colonel Ross and his wife (Lynn Loring) have a loveless sham of a marriage. They cheat on each other and the wife shrewishly blames him for the fact that she is childless. When Ross finds her birth control pills, he slaps her across the face hard enough to knock her to the floor. You didn’t see that in Thunderbirds.

The mission launches and the Astronauts are put into a kind of cold sleep. They wake up when they reach their destination, and the planet appears to be quite habitable. However, the landing goes wrong and the lander is destroyed. Kane is critically injured. Ross is facing the terrifying prospect of life alone on an alien world when a Mongolian search and rescue team shows up. He’s back on Earth…kind of.

It was supposed to be a six-week journey, but they were back in three. Director Webb is incensed and is in a rage to find out why Ross turned back. Ross maintains that he didn’t. Some stuff happens and some hints are given. Ross is seeing all writing in reverse just like you would in a mirror. The light switches in his home are on the opposite walls. Kane dies and the autopsy reveals that his organs are all on the opposite side of where they should be.

Ross finally realized that he did complete his mission and made it to the planet on the far side of the sun. The planet he is on is the equal and opposite of his Earth.

Webb agrees that he’s right and tries to send him home. It doesn’t work out because the fucking polarity was reversed on the capsule, so Ross crashes dramatically and dies tragically. Derrick Meddings had a really first-rate explosion there.

On the off chance, you want to see this one, I’ll not say anything about the very last scene but it is a pretty good one.

Admittedly, not many people did see this movie in 1969.

Doppelganger bombed and the Andersons never got another theatrical release. Although by then they may not have cared that they never got another shot at the big movie brass ring. By all accounts, it was the production from hell from start to finish.

The lead actress quit at the last minute and Roy Thinnes’s own wife (Lynn Loring) had to step in. Derrick Meddings ran into a lot of trouble with his models because he had never worked at this level of detail before. Things that wouldn’t be seen on a 13-inch TV were going to be spotlighted on a theatrical screen. Meddings came through but his learning curve was expensive.

Patrick Wymark and Ian Hendry not only were openly hostile to each other but were both far gone in terminal alcoholism that was bad even by 1960s British standards. Director Robert Parrish was eventually forced to shoot their scenes as early in the day as possible before they could get too loaded to work. Wymark in particular is red-faced and looks puffy from his first scene to his last. Although it did add verisimilitude to his performance as a man with a heart condition, he looked like a man in his early sixties who wouldn’t make it to his seventies.

Patrick Wymark died of a heart attack the next year at the age of 44.

I think its biggest problem was that the premise was too silly for the audience to buy. Maybe you could have gotten away with it a few years before but by 1969 audiences were too grounded to accept it. The movie missed too many obvious problems with its orbital mechanics. People around the world had watched the Apollo landings and had newsreaders explain to them repeatedly how you couldn’t just flip the ship around and go back. Audiences knew all that at the front of their minds in 1969. Also, the ship returning in three weeks when it would have taken six to complete the journey was a screwup with some very basic math. Then there was the fact that Colonel Ross was the hero of the Martian Expedition. If he had been to Mars, he would have been the first to know that there were two Earths. Although, running into himself would probably have been more of a giveaway.

At the end of the day, Gerry Anderson was out of his league. He had written some all-time great kid’s shows and while he proved to be decent with adult-themed characterizations, he hadn’t worked with them before. It was all too ambitious for what he had been doing up until then.

The movie was not a failure in every way available to it but that’s not exactly high praise.

That said, it did pave the way for Century 21 to make the two biggest TV series it would ever make. Doppelganger pretty much paid for UFO. In some ways, it was a preview. The props and sets were redressed and used wherever possible. For that matter so was the cast. The second-string performers were Century 21 regulars like Ed Bishop, George Sewell, Keith Alexander, and Vladek Sheybal. They got bumped up to the front seats for UFO.

Does it hold up? That is always the big question for a RE:View and surprisingly, the answer here is, yes. It does hold up.

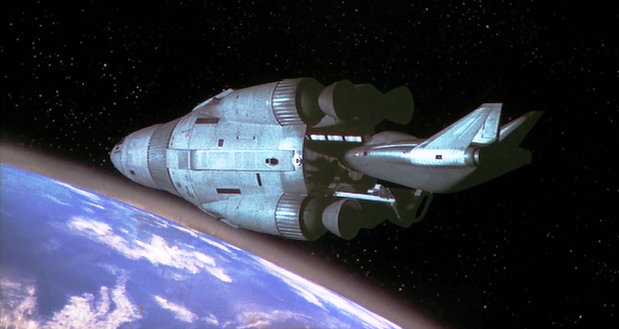

The only reason there ever was to see this movie is the special effects.

I admit most of my trip down this memory lane had to do with taking time to enjoy Derrick Meddings monochrome monomania. What I love about his work is the combination of the fantastic and the grounded in reality. His wonder machines had to be able to work, at least in theory. There wasn’t the attitude you clearly see from Star Wars (1977) of “let’s just kit-smash for a while until we have something that looks good.” As fantastic as it was, he always built something that felt real.

“Thunderbirds marked the point where Derek Meddings and cohort Mike Trim started working in tandem: Meddings designed much of International Rescue’s core craft, prioritizing sharp bulk and heft, while Trim took care of secondary/guest vehicles, producing more streamlined and sinuous craft. The aerial gymnastics of the sleek, supersonic first responder Thunderbird 1 starts the action of each episode, complemented by the lumbering, powerful Thunderbird 2, the most recognizable of all of the Andersons’ mecha and a craft that fills the screen whenever it takes off, soars through the skies, or lands in some danger zone. Thunderbird 3 is more of a curiosity, since we only ever see it in a handful of episodes, yet it remains another of Meddings’ fascinatingly gargantuan designs. The trim, squat Thunderbird 4 is everything Supercar should have been, while the immobility of space station Thunderbird 5 is at odds with its sophisticated, complex design and exposed mechanics.

The separate functions of each of the five Thunderbirds gives the show a visual depth and sense of scale. No one Thunderbird performs the same function, and that specialization enables International Rescue’s daring and eye-catching missions to be fully realized. Thunderbirds distinguished itself from past Supermarionation fare by not placing all of its toys in one sandbox: the aerodynamics of Thunderbirds 1 and 2, the space-based Thunderbird 3, the sub-aquatic Thunderbird 4, and the watchful, sentinel-esque role of Thunderbird 5 gave the series its panoramic sense of adventure.

No one will ever put Doppelganger in their top ten list of sci-fi movies. But given the care that went into it, you will never find it at the bottom of those lists either.