The Collapse of Gaming Journalism

Last month, IGN decided that the hill to die on this week was Palestine. They printed some article on giving aid to Palestinian Children* that I didn’t care about and didn’t read because I haven’t read anything from IGN for years and I wasn’t starting now. However, IGN Israel did read it and screamed at the corporate owners. Ziff-Davis roused itself from its dreamy lassitude and made the accurate but surprising decision that this article had nothing whatsoever to do with gaming or popculture and spiked it.

IGN America screamed journalism rape and railed at their corporate owners in public. Doesn’t Ziff-Davis know that IGN is a serious professional media outlet

Smelling blood in the water, various YouTube channels started tearing shark-like into the chum bucket that is mainstream gaming media in 2021. Naturally, the Blue Check Mark Mafia started crying about Alt-Right YouTubers like Clownfish TV, The Quartering, and Vito. If you are familiar with any of these personalities, you know how much of a joke this is.

None the less gaming journalists are screaming about they are under siege because people are criticizing their opinions. And worse still are ignoring them as completely irreverent when they are in fact, important journalists even if their eyeball numbers are in the basement.

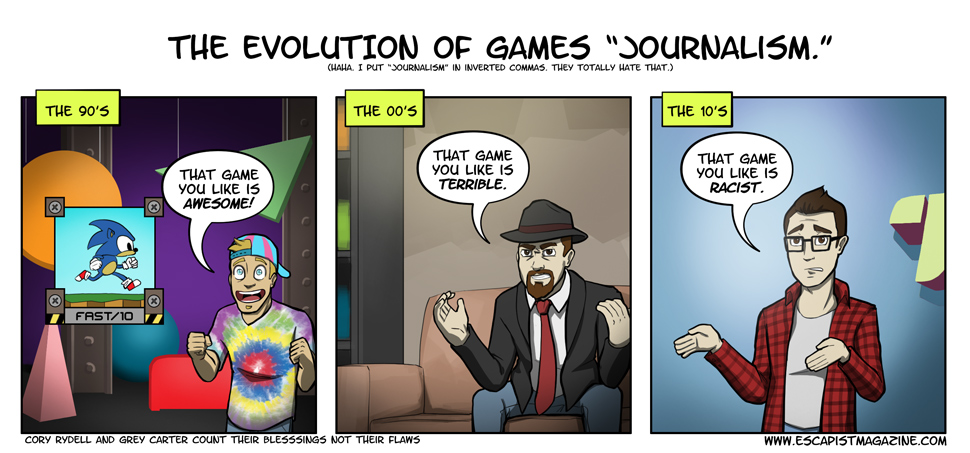

Gaming journalism is now a sad laughable failure that is a caricature of its former self.

How did it get this way?

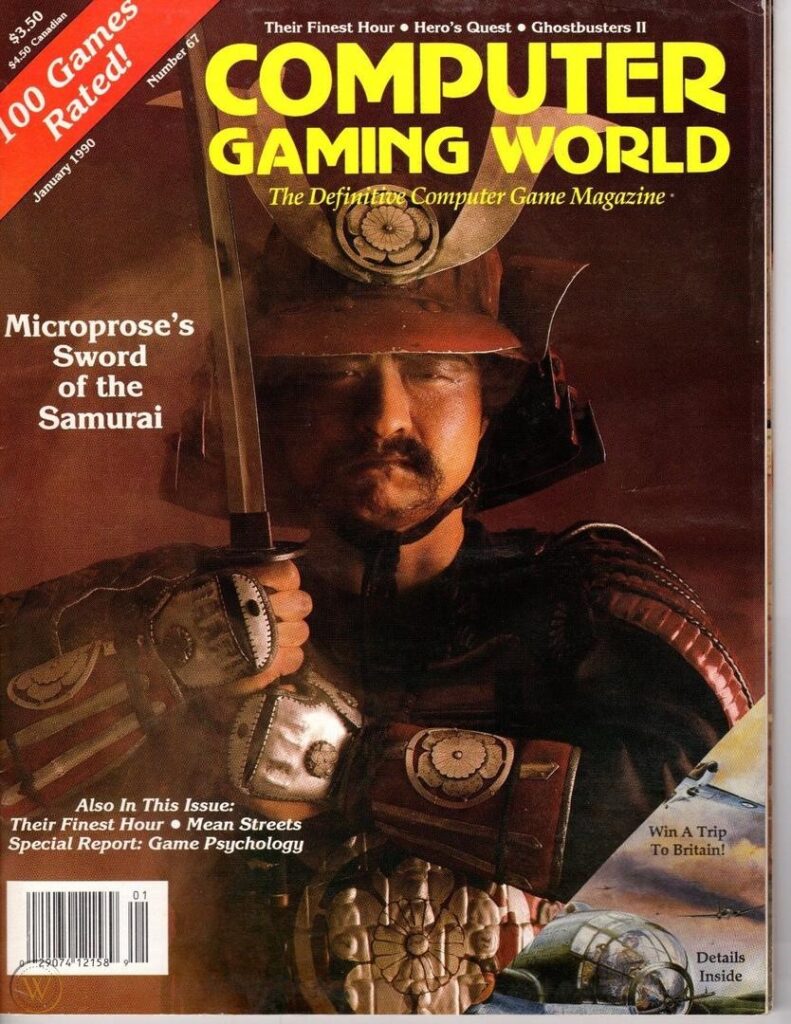

Back in the 1990s I had a subscription to Computer Gaming World. It was a don’t miss back then.

Given what the internet was like back then, a print magazine was an absolute necessity. At least if you were going to find out if Master of Orion II was anywhere near as good as the first game, (BTW, it was better). Is the full version Redneck Rampage as difficult to run as the share-ware? (Yes, definitely). Or is John Romero really going to make you, his bitch? (No, he wasn’t.) You would also get interviews with people like Roberta Williams and Richard Garriott. Plus, you would find out which conventions were going to have the best computer gaming room. (It mattered in those days because it might be the only place you could play some titles if your friends didn’t have a copy.)

Here’s the big thing. There was a real sense of community back then and gaming magazines were the glue that was holding us together. The guys that wrote those articles were part of our tribe. They spoke our language, shared our concerns, and agreed with us on what was cool.

The gaming magazines were huge and don’t just mean within gaming culture. They were physically gigantic. There was a point where CGW had 500 pages. That was where the trouble began.

When you have that many pages, you need to fill them with something. The editors of gaming magazines had run into a problem there. They could hire more gamers and teach them how to write, a longer process to be sure but in the end, you would have more in-depth articles by people who know and love gaming. However, given how fast the gaming magazines were growing and how much original content they needed month to month, a shortcut beckoned siren-like to the editors.

There was always a pile of resumes from journalism majors who were shotgunning any publication in the hopes of getting a gig. They knew absolutely nothing about gaming, but they did know how to write, (sort of, they were journalism majors after all). The view clearly was, just give them something easy to play until we can find someone better,

So, the editors started hiring journalism majors as a temporary shortcut. The kind of temporary shortcut that stays forever. Journalism majors could write about games, but they didn’t love them. They didn’t care at all about game mechanics, what they had a passion for was narrative story structure and pretty, pretty pictures. So long as a game had those it would get a ten-star review even if the gameplay sucked.

It was obvious that these journalism majors were setting the game difficulty on Toddler Mode and playing through as fast as possible. They wanted to experience the narrative with as little interruption by gameplay as could be managed.

This temporary fix stuck around. The journalists got promoted. Then the magazines started getting bought by media conglomerates like Ziff Davis, who definitely preferred to work with journalists. Consequently, the gamers at the gaming magazines got shunted to the side and the journalists started making the hiring decisions. Guess who they hired?

You guessed right. Other journalists.

The other thing you have to remember is why college kids got into journalism. There had been a time when news media ran on an apprentice system. Papers would hire stringers who provided news tips, the best of these got taken on as cub-reporters and were taught how to write and what the rules of the game were.

Then came All the President’s Men and the myth of the crusading liberal activist journalist was created. Journalism went from a blue-collar profession to strictly white-collar college graduates. A big part of this was the fact that by the Seventies, we had too many elites and nowhere near enough elite jobs. This was the point where we first saw the plague of lawyers erupting out of law schools. But if you weren’t smart enough to get into law school, you could be a journalist. Anyone could do that. If you asked a Journalism major why she wanted to get into the field the answer was invariably, “I want to change the world.”

Forgive me for stating the obvious but if you are trying to change the world, instead of reporting events factually, then you are a propagandist.

The new breed who had taken over gaming journalism wasn’t part of the gaming community, but they did want to tell it what to like and what to think. Games with a left-wing slant started to reliably get better reviews than ones that didn’t. The game devs noticed and started adjusting their narratives accordingly.

Narrative became ever more important than gameplay.

If you want a perfect example of where this led, in 2013, Irrational Games, delivered one of the dullest games I’ve ever played. Its title was as clunky as the rest of it, The Bureau: X-Com Declassified. It started as an FPS but then Mass Effect blew up big, so it was turned into a third-person shooter. This thing was an overblown rail shooter. You were very firmly welded into a predetermined path of events that would lead from cut scene to cut scene to cut scene. Getting the player to trigger cut scenes was the real objective of this game. The game stuff that happened in the middle was incidental.

2013 was the year that Zoe Quinn launched Depression Quest. A game that got aggregate scores of 9.0 for gaming journalists and 0.9 from gamers.

You know what came next.

End of Part 1

*There was a major side issue here. If you know anything at all about Arab charities, then you know damn good and well that the money was going straight into someone’s pocket. Arabs don’t do impersonal charity. Your tribe is supposed to take care of you. If you accept charity from a stranger, especially a Christian it’s an insult to your tribe.