RE:View Star Trek The Motion Picture

One of my earliest memories is the landing of Apollo 11. My parents woke me up for it and dragged me downstairs so that I could wobble bleary-eyed on my father’s lap as Eagle came down to rest at Tranquility Base. I couldn’t make out what Armstrong said. The interference was bad that morning. But even at that age, I knew that I had just watched something that was supposed to be important.

Because everyone kept telling me it was.

Apollo 11 was the Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria all rolled into one. Armstrong was the new Columbus (For the benefit of Millennials and Zoomers; fifty years ago, Columbus was generally admired in this country. No, really, he was.) A new world was opening up and I as an extremely young child was told constantly that I was going to be a part of it.

The Moon was just a stepping stone. The real first step would be Mars. Then would come Jupiter, Saturn next, the outer planets, and… Well, that would probably have to be it for my lifetime. FTL travel was as elusive then as it is now. But an entire Solar System was likely to be the work of a lifetime. There was zero doubt at that moment that we would soon be headed out to the rest of the Solar System.

Star Trek had already been canceled for a month.

My first memories of Star Trek are not much clearer than Neil Armstrong’s walk-about, and they mostly involve my father saying, “Hell no! This is my house and I paid for this damn TV set. We are watching Laugh-in!” There was of course only one TV in the house. My memories of Laugh-in are resentfully blurry.

Regardless, I was promised that I could watch Star Trek during reruns since Dad didn’t care to laugh at the same joke twice.

And boy-howdy was Dad right. I certainly did get to watch Star Trek in reruns. Star Trek the original series was in syndication pretty much continuously until Next Generation came along.

Despite its short run of 72 episodes, it became the most influential science fiction TV series of all time. I’m not exaggerating. Everything that followed Star Trek, either had to implicitly accept or reject what it had brought to the table.

This is not to say that it was good.

A thing does NOT have to be good in order to be influential it just has to have a big footprint. In the days of three networks and not much in the way of other science fiction shows on the air or most especially in reruns, Star Trek couldn’t help but have a big footprint. For ten years there was rarely anything else out there. UFO came and went in one year. Space 1999 lasted two seasons and then vanished from the air. There were several one-season wonders and a bunch of pilots that never got picked up, I’ll get to that shortly. But nothing challenged the impact of Star Trek because nothing could.

The reason was that nothing lasted long enough to be in syndication.

In the days before cable, syndication was everything. That was the market that made money for the production companies. When a show was on the air for the networks it was basically being made at cost. There was no profit to be had by the 1970s. But when a show got picked up for the rerun market the money could come raining down for years and the production costs were zero. Reruns were one hundred percent profit.

But, and this is the important part, you needed a minimum of seventy-two episodes. At seventy-two, Star Trek just barely cleared the wire.

That odd little rule kept Star Trek the Original Series on the air in every market for better than twenty years. It gave Star Trek time to not just move the needle but to set the standard because there was no other science fiction show that had that kind of legs.

In truth, it has not stood the test of time as a whole. Watching it today tends to be something of a disappointment. You remember it as being better than it was.

The sets look cheap, and the lighting looks awful. Shatner’s typical performance was hamtastic but he was hardly alone there, as the entire cast was either completely wooden or absolutely over the top. A lot of the stories were silly as hell. Although granted, a few of them weren’t. They weren’t bad actors, but they had to compensate for television reception that was frequently snowy, and often nearly unwatchable. Over acting was the only way to get their performances across. It was part of the reason, TV was looked down on in the industry.

The Star Trek episodes that weren’t terrible all had one thing in common. They had been either written or produced by Gene L. Coon.

One of the big differences between the original series and those that followed it was the mindset of the men who produced, wrote, and indeed watched it. All of them had been in uniform at some point in their lives. The post-World War II paradigm predominates throughout the original series.

The Cold War Draft had shaped American society in a way that no one can comprehend today. Between 1940 and 1973, when a young man reached eighteen years of age he was presented with a choice.

1. Pick the service of your choice and volunteer. Volunteers received preferential treatment, MOSs, and assignments. Volunteers are always preferable because their morale is fundamentally better. If for no other reason than you can always throw it in a Volunteer’s face. “Hey, you volunteered shitbird. Nobody asked you to be here. You wanted this.”

2a. Request deferment for college and then go in as an officer. If you have to be in the band, you are better off being the guy waving the stick.

2b. Become something that the US government did not want to be drafted at all. Doctors, scientists, engineers, and the like. Even, farmers past a certain point.

2c. Get married in college and have a couple of kids. That usually got you out of the running. Particularly if your new father-in-law was somebody who could go cry for the local draft board on your behalf.

3. Last choice for anyone. Take your chances with the Draft Lottery.

In short, the Draft had been used as a very effective club to motivate the young men of America. The Draft had become a societal engineering tool. The exemptions to it strongly influenced the choices of young men to proceed along paths that American Society most approved of for them. Regardless of how they felt about it personally.

And I can only imagine the horrible choices that would be forced upon young men today if the Draft was still on.

Star Trek the Original series is a product of that America. And this is the important part. A lot of hardcore Lefties who would never have considered such a thing did time in the military.

And Star Trek was Lefty as fuck. When it started production, written Science Fiction leaned to the right. No, I’m not joking here, it actually did. The influence of John W. Campbell had been immense in the field. If you wanted to get anywhere as a Sci Fi writer then you adjusted your opinions to please him.

Gene Roddenberry on the other hand was a Mercedes Marxist who could never afford the Mercedes.

He started out as an LA cop in the 1930s. Then flew B-17s during the war. He became a commercial pilot after the war and following a nasty crash in North Africa went back to being a cop. While being a cop he became an adviser to the legendary crime procedural drama, Dragnet. I have a suspicion that he was the inspiration for “Hollywood Jack” in LA Confidential.

Dragnet was Roddenberry’s entry portal to TV. He worked as a scriptwriter on cop shows, westerns, and military dramas. He combined all three when he pitched a Sci-Fi show as “Wagon Train to the Stars.”

The first pilot is quite interesting as it is Roddenberry’s closest iteration of what he wanted Star Trek to be, and The Cage has almost no resemblance to the original series. Stark, dark and gritty come to mind when describing it. Starfleet was an actual military organization. It reflected Roddenberry’s own experiences in the Army Air Corps. The captain of the ship was more fighter jock than Horatio Hornblower. There was a ship’s doctor who acted as the older man counselor to the captain. The Enterprise had an actual CPO and that never happened again. Proto-Spock was there but he was just some guy with pointy ears and obviously had emotions.

Roddenberry’s creepy sexual interests were very much on display as well in this show.

Captain Pike’s Number One was a woman. Which in a more Game-aware and military-aware world could have worked. The XO is inherently a more maternal figure in the military hierarchy. The sympathetic agency that can be appealed to, and one that is inwardly focused on the running of the organization. In short, the XO is the Mom who wears the pants in the family. But the Number One character very definitely had a dominatrix vibe about her. Then there was the innocent, inexperienced country girl yeoman, who clearly had a crush on Captain Pike. Finally, we had Vina. The woman that could change to fulfill any male fantasy. All three were presented by the alien overminds for Pike’s pleasure.

Roddenberry was the proto WorldCon goer in this regard.

The first pilot was scrapped but a second was ordered. This new one was less militaristic in nature but still didn’t feel like Star Trek. Roddenberry stayed true to his horrible vision for the first 13 episodes.

His vision of the future, by the way, didn’t include the likes of us. We were pretty much expected to conveniently die-off in WWIII. This event was hinted at very strongly throughout the series but was never fleshed out in much detail. Which was typical for the sixties. Everyone expected the Cold War to one day turn hot and this expectation strongly influenced the show.

This cleansing by fire would exterminate all primitive thinking nationalism. Only noble, scientific globalism would remain. Ready to head to the stars. Even here Roddenberry was an unoriginal hack. H.G. Wells had laid out that future decades before.

Roddenberry’s insecurities were apparent from the start. He fought with the studios, the network, the writers, anyone who crossed his path. “During the first year,” he says, “I wrote or rewrote everybody, even my best friends, because I had this idea in my mind of something that hadn’t been done and I wanted it to be really there. Once we had enough episodes, then the writers could see where we were going, but it was really building people to write the way I wanted them to write.”

Except that isn’t what happened because Roddenberry never stopped rewriting. “The problem,” says his biographer Joel Engel, “was that he basically couldn’t write well enough to carry it off.” A script never left Roddenberry’s hands without becoming worse.

Then along came the unsung hero, who is unsung because Roddenberry wrote him out the picture completely and in a world before the internet, you could totally do that.

Gene L. Coon is the real creator of Star Trek. He was brought on board to be the showrunner after Gene Roddenberry lost interest in the project. Coon is the one who created every hallmark of Star Trek. The United Federation of Planets, the Klingon Empire. Starfleet Academy, Starfleet Command, and of course KHAAAAAANN! He oversaw the second and truthfully only good season of the show.

Roddenberry couldn’t forgive him for being more talented than he was. He eventually forced Coon off the show and took credit for everything he did.

That didn’t play well in certain quarters.

“Shatner actually took it up a notch while the “Great Bird of the Galaxy” was still alive. Even though he had not nearly as large a bone to pick with Roddenberry as, for example, his co-star Leonard Nimoy had, Shatner apparently felt damned if he would let Roddenberry get away with the perceived injustice. On 6 June 1991 shortly before celebrating the 100th episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, the Producers Building at the former Desilu studio lot was renamed “Gene Roddenberry Building”, and Shatner was one of the speakers at the dedication ceremony. During his speech, Shatner purposely dropped Coon’s name a few times, in an effort to embarrass Roddenberry. Very shortly after Roddenberry’s death five months later, Shatner, not in the slightest rueful, explained himself, “In my opinion, Gene Coon had more to do with the infusion of life into STAR TREK than any other single person. Gene Roddenberry’s instincts for creating the original package are unparalleled. He put it together, hired the people and the concept was his and set in motion by him, but after 13 shows other people took over. Gene Coon spent a year and set the tenor of the show and there were several other producers who were writer/producers who defined its character. Gene [Roddenberry] was more in the background as other people actively took over.” (Cinefantastique, Vol 22 #5, p. 39) Shatner in particular, has not let the issue slide, nor did he mellow over time, when he, as late as 2008, wrote in even harsher tone in his autobiography, Up Till Now: The Autobiography, “After the first thirteen episodes writer/producer Gene Coon was brought in and Roddenberry became the executive producer, meaning he was more of a supervisor than working on the show day -to-day. After that his primary job seemed to be exploiting Star Trek in every possible way.”

Coon died long before the Star Trek’s rise to pop culture dominance in the 1970s.

It was during that period that Roddenberry showed his true genius…as a marketer. And what he was marketing was a product called Gene Roddenberry, Genius. He didn’t actually produce anything to back this up.

Here is a quick rundown of his failed pilots: Questor Tapes about a sapient android that was part of a conspiracy to save the world through globalism. Genesis II, which was a Buck Rogers scenario about a 20th-century scientist trying to bring about globalism in a post-WWIII world. Next, Roddenberry kind of went back to his roots with Haven/Future Cop (it got two pilots with different names) about an android cop. A second version of Genesis II, this time starring John Saxon. And finally, Spectre, which was basically a supernatural Sherlock Holmes and it isn’t anywhere near as good as it sounds.

All of these shows found time for some kind of creepy sex thing. Questor Tapes had the robot bang a woman because “he was fully functional in every way,” (Roddenberry must have thought that line was gold because he recycled it in STTNG). Genesis II had our hero in a coma until a mutant woman smashed him into consciousness. The reboot of Genesis II featured John Saxon as a sex slave. And Spectre had a scene of nonconsenting sibling incest.

These turned out to be unimportant side projects for Roddenberry.

Just something to keep the lights on because as the seventies wore on it was becoming obvious that sooner or later Star Trek was going to rise from the grave.

The show had gone from canceled series to unheard-of pop culture phenomenon. Dedicated Star Trek conventions had begun springing up everywhere. New books and comics were constantly being published. There had been a cartoon revival. And the toys were selling better than when the show had been on the air. Mister Spock was being used to market everything from breakfast cereal to lunchboxes to Heineken beer.

Although, at times there was considerable doubt that Star Trek would be back. This was largely due to Gene Roddenberry’s talent for self-sabotage.

The first attempt at a Star Trek film was taken from green light to red light because of Roddenberry’s constant demands for incompetent artistic control.

Star Trek was on the backburner at Paramount for a while, but after Star Wars came out, interest at Paramount drastically escalated. A second live-action series was planned. Star Trek Phase II. And an entire first season of scripts was written. Most of the cast had been out of work for years so they were happy to have jobs again.

Leonard Nimoy, however, was OUT, he wanted no part of it. He had signed a contract back in 1966 that gave Paramount the right to use his, which is to say, Spock’s face for marketing purposes in perpetuity. For which he received the princely sum of $0.00. By the late seventies, Paramount was plastering Spock’s mug on everything from breakfast cereal to lunchboxes to Heineken beer.

And every time Nimoy saw Spock’s face his blood pressure went up. At one point he told his agent, “I will fire you if you ever mention Star Trek again.”

However, William Shatner was willing to come back (better contract).

A new character, Will Decker was going to be Kirk’s XO and a new Vulcan was going to be the science officer. A beautiful alien from a race that was as sex-obsessed as Roddenberry himself named Ilia was also added. Because it was a Gene Roddenberry production, it was already running into problems before the first foot of film was shot.

And then Paramount’s owner, Gulf & Western heard about Star Wars, and the CEO called to ask Paramount, ‘Don’t we have something like that?’ Michael Eisner (Paramount’s president at the time) replied, ‘Yeah, we’re making a TV series out of it.’

‘No, you’re not.’

The series was instantly scrapped in favor of a robustly funded theatrical release.

When Star Trek the Motion Picture began production Roddenberry’s inner id went off the leash.

Gene Roddenberry himself was something of a Player. Which is unsurprising, he was a bomber pilot, turned airline pilot, turned cop, turned Hollywood producer. The personality archetype is present in all of these professions. And in the best of aviator and Hollywood traditions, he fucked around on his wives constantly. He was given to keeping long-term mistresses on call and providing them with whatever employment he could send their way. Which is how we got Uhura.

However, he wasn’t Don Draper. Sex wasn’t something he could take or leave. He wasn’t the master of his desires. Roddenberry was as sex-obsessed as Hugh Heffner and he was very weird about it.

That is clearly reflected in the first draft of the script for STMP.

“Harold Livingston wrote the first draft. As usual, Roddenberry rewrote it. ‘Then he brought it in,’ Livingston says, ‘he gave it to us in a bright orange cover, and there it is: In Thy Image, screenplay by Gene Roddenberry and Harold Livingston.’

He took first position. We all read it and I was appalled, and so was everyone else. We sat around looking at each other and somebody said, ‘Who’s going to tell him it’s a piece of shit?’”

The draft was marked November 7, 1977. Roddenberry’s opening scene: Kirk and a lady friend skinny-dipping. Starfleet hails. But Kirk is distracted when his girlfriend pulls him underwater. After a beat he surfaces, responds to the hail, and says, “I was attacked by an underwater creature.” There is more. The crew of the Enterprise is sent to investigate a mysterious probe heading towards Earth.

In one scene, “shapely female yeoman checks out the young and inexperienced Xon, straight out of the Academy and the new science officer, and asks him about pon farr,”.

Admiral Kirk tells another new member of the crew, the empathic Ilia from the planet Delta, “I know that Deltan females are not wanton, hairless whores.” At this Ilia laughs and says, “On my world, existence is loving, pleasuring, sharing, caring.” Kirk asks, “Have you ever sexed with a human?”

It isn’t just creepy, it’s also embarrassingly bad writing.

Another problem STMP had was that Roddenberry was determined to recycle story ideas that he had had for his shows that never got picked up.

According to Harlan Ellison, the plot of STMP was based on a script for Genesis II called The Robot Returns, which was itself a rewrite of The Changeling episode (Nomad) of the OG Star Trek. He was also working in as many elements from Star Trek Phase 2 as he could. Will Decker and Ilia the Deltan female were ported in. Apparently, the answer to Kirk’s question was ‘yes, and with Will Decker.’ The new Vulcan on the other hand would have to be disposed of. Given how badly they needed Mister Spock, Paramount finally bit its lip and paid up big time. Leonard Nimoy was now in.

There are contrarians out there who will claim STMP was the best of the Star Trek movies.

It isn’t.

It had several major problems, but I think its biggest was character development. James Kirk was Roddenberry’s self-insert Gary Stu. Roddenberry was 56 when he started writing the script, his standing on the SSH was dropping like a stone, and he couldn’t deal with it. He wanted to turn back the clock and that was reflected in all of Kirk’s actions.

James Kirk had been promoted a couple of times and was now an Admiral. And he was clearly terrible at it. Rather than pursuing and embracing the greater responsibility of commanding a fleet, he was determined to go back to single-ship command. The moment he got a chance to do so, he stripped Decker of his captaincy, which bluntly is unthinkable unless the guy is a total boob, and in that case, you kick him off the ship entirely, then replace him with another Captain.

Kirk pretty much steals the Enterprise for himself on the grounds of “I’m the best Captain there has ever been.” And then he repeatedly mucked things up afterward. A more realistic approach would have had Kirk transferring his Admiral’s flag to the Enterprise and informing Decker that Starfleet wanted a Flag Officer in overall command of this operation. Decker would obviously still be commanding the Enterprise.

Taking the Enterprise for himself was a cheesy way of creating conflict between the two men and Decker was clearly the wronged party. It didn’t feel like something that the established character of James T. Kirk would have ever done. I suspect if Gene Coon had been alive he would have pointed out the obvious solution of making Kirk a Fleet Captain (an established rank in the OG series (S3E14: Whom God’s Destroy), and just get rid of Decker.

There was also way too much, ‘We’re getting the band back together.’

There was no need at all to bring back the original bridge crew. They were all in their 40s by the time shooting started, they had all aged out of their roles. After twelve years these Starfleet officers were still in the same jobs? It didn’t make sense in terms of canon unless being on the Enterprise was the worst career move in all of Starfleet. Younger, sexier replacements would have made more sense. If you must have memberberries then have Sulu, Chekov, and Uhura commanding ships that were trying to rendezvous with Enterprise but couldn’t get there in time.

I suppose Scotty needed to be in the engine room. That was kind of a given. His character was always going to be static, so you could picture him being stuck there and not minding in the least.

Now it was absolutely necessary to have the big three of Kirk, Spock, and McCoy or it wouldn’t be Star Trek.

However, Spock’s character arc was just terrible. For ill-defined reasons, he had been trying to become a completely unfeeling super-Vulcan and then he gave that up by the end of the film to go back to being regular Spock, making him another character whose character arc was turning back the clock. Basically, Spock’s part was written at the last minute because Roddenberry didn’t know if Nimoy was coming back. Nimoy liked his shiny new contract but hated the material that Roddenberry slapped together at the last minute. By the time the film wrapped he was swearing he was out for good this time.

McCoy, however, was fine. Making him older and grumpier was all you ever really needed. His character was always going to be as static as Scotty’s. Although, having him terrorizing a young doctor in her residency aboard Enterprise might have made more sense than bringing him out of the reserves.

There were other issues. The film was too slow and too long. If this was supposed to be Star Trek’s answer to 2001, fine. But it wasn’t. This was just a matter of poor pacing and following a romantic subplot whose only real purpose was to get Decker out of the way permanently, meaning he served no purpose in the first place. And as I said, the main storyline had been repeatedly recycled by Roddenberry.

The film’s biggest problem was the Peter Principle. Gene Roddenberry had been overpromoted. He had helmed plenty of TV projects, but he had never produced a big-budget Hollywood theatrical release in his life. He didn’t have the necessary skill set to do so and at the age of 57, he seemed determined not to learn. The stream of rewrites was constant, with the actors frequently getting their lines on the day of shooting.

While the sets were okay, the costuming was a product of early 1970s futurism and was way out of date in the post-Star Wars world of 1979. These uniforms looked like pajamas.

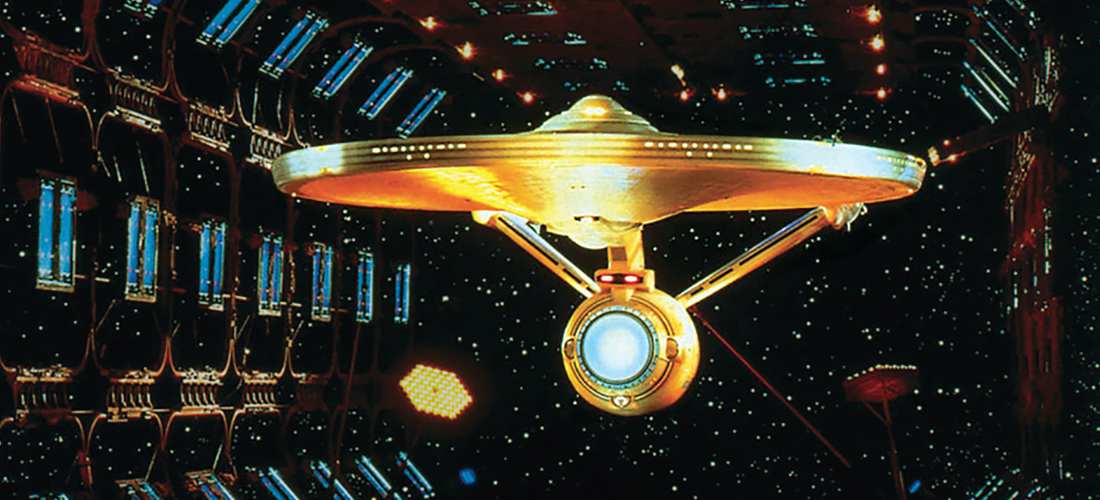

On the plus side, Robert Wise was about as good a director as you could get for the project. He was familiar with science fiction and knew how to make a film look like an epic.

But epics are never cheap, and money was becoming an issue fast.

Aside from Roddenberry’s unending barrage of script and costuming changes, he had picked the wrong guy for special effects. Star Wars had changed everything, but nobody had yet been able to duplicate Industrial Light and Magic’s… Well, magic.

Robert Abel was a pioneer of computer-generated special effects and would become a legend in the Eighties, but he hadn’t been able to get his own system of computer-controlled cameras and models synched up. None of the model footage he had produced was of theatrical or even TV quality. Although, some of his computer effects made it into the final film.

As the expenses moved north of $30 million on a film that was budgeted at $10 million, Michael Eisner went into panic mode. Studios had a lot less money to play with in the 1970s. And Star Trek was now a potential studio breaker.

Douglas Trumbull was finally strong-armed into taking over the effects for Star Trek. Roddenberry wanted to make his life difficult too, but by then Michael Eisner had taken a very hands-on approach with STMP. For once studio interference saved a movie.

It raked in 85 million at the box office, but it was a hair-raising few months at Paramount before that happened.

Paramount was done with Gene Roddenberry.

His job title was changed to Creative Consultant, and he was quietly kicked off the movies. So, we never got to see the one where the Enterprise travels back in time, Kirk becomes besties with John F. Kennedy and Spock is the shooter on the Grassy Knoll. I’m not joking about any of that, Roddenberry tried to sell that script for years.

So does it hold up?

In a way, yes. I’ll say this for it. It’s as good as it ever was.

Star Trek the Motion Picture’s foundational problems don’t detract from the fact that it was the most epic of the ST movies to include Abrams flicks in my opinion. The model work has held up. The score was great. It’s not the best of the Star Trek movies but it’s pretty far from the worst. I can recommend with confidence the Robert Wise Director’s Cut. It was a top-notch remaster from a time when films were a product of genuine craftsmanship.

Star Trek the Next Generation suffered through its first couple of seasons for the same reasons that everything else touched by Roddenberry turned to shit. Although, in that show’s case, it was rescued in the third season by Roddenberry’s health issues brought on by too much booze and coke.

He had to step aside and let the show be taken over by younger men who had been inspired by Gene L. Coon. Even if they thought they had been inspired by Gene Roddenberry.

He contributed nothing to the best of the movies, Star Trek II The Wrath of Khan but that’s another RE:View